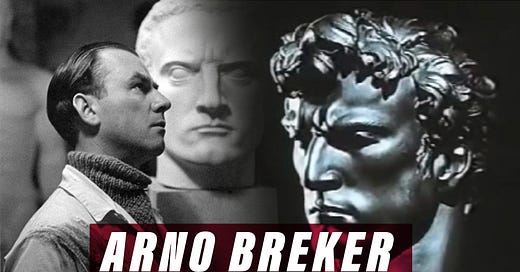

In recent times, one of the many neoclassical artists to see a return to popularity has been the German sculptor Arno Breker. He had worked for the Reich in the 1930s, and remains a somewhat controversial figure, yet respected within his field of expression. Many are familiar with his works, but few know much about the man behind the sculptures. So, who was Arno Breker?

ORIGINS

Born in 1900 in Elberfeld, Germany, Breker was the son of a stonemason. From an early age he showed an interest in stone carving, likely due to his exposure to his father’s stonemasonry, and took up the study of stone carving, as well as anatomy and architecture. By age 20 he was a student at the Dusseldorf Academy of Arts with a focus on sculpture. He studied under several prominent German artists, notably the well-regarded architect Wilhelm Kreis, who would go on to work for Albert Speer, and the sculptor Hubert Netzer.

In 1924, nearing the end of his studies, he visited Paris, making acquaintances with Pablo Picasso, Jean Renoir, and Jean Cocteau, among others. By 1927 he had moved to Paris and developed many important friendships in the art world, including such figures as Isamu Noguchi and Charles Despiau. He held an exhibit alongside fellow sculptor Alf Bayrle, and considered Paris to be his home although he would travel through North Africa and win a year in Rome in 1932 courtesy of the Prussian Ministry of Culture.

During this time, Breker befriended artists from all backgrounds, American, Japanese, Jewish, French, and one particular friendship with Max Liebermann, who had an enduring effect on him. Liebermann suggested to Breker to move back to Germany, which he did in 1934, albeit with some reservations. Unfortunately for Liebermann, he would soon be shunned from Germany due to his Jewish heritage. Yet Breker never renounced his friendship with the Jewish artists, and it is not evident that Breker was ever a political ideologue for the regime.

Brecker’s friendships with people like Liebermann did have negative consequences for him when he returned to Germany. Most notably, the highly influential, highly ideological Alfred Rosenberg attacked Breker, claiming that he created degenerate art. This criticism, unsurprisingly, was also toward Max Liebermann and most Jewish artists. Ironically, Liebermann’s work was far from the abstract degeneracy Rosenberg was alluding to, in fact most of his work avoided abstraction, being of coherent form and rendition, portraying European culture. Liebermann vocalised how he felt betrayed by the culture he had tried to integrate into. The claim from his adversaries was that his advocacy for realism over romanticism was somehow allowing for Jewish subversion. Evidently, it is hard to view his art and come away with this impression. He would die soon after Breker’s return to Germany. Breker would return to see Liebermann after passing, creating his death mask.

Breker continued to persevere with his art, despite Rosenberg’s attacks, and would find favour as an artist in Germany. Fortunately for Breker, Rosenberg’s insane and often esoteric rhetoric was seen as unhinged by the top German leadership, and even Hitler himself became a fan of Breker’s art. In fact, Rosenberg, likely under pressure from the vast majority of Nazi leadership who enjoyed Breker’s work, would later repent, claiming that Breker was a visionary portraying might and willpower.

Breker’s two primary friendships in Nazi Germany would be Hitler, for his obvious appreciation of art, and Albert Speer, for likely the same reason. Yet it remains a matter of speculation whether he actually supported the ideology of the party, and whether he kept distant from other high ranking ideologues within the regime, such as Rosenberg and Goebbels, who had great influence over German art at the time.

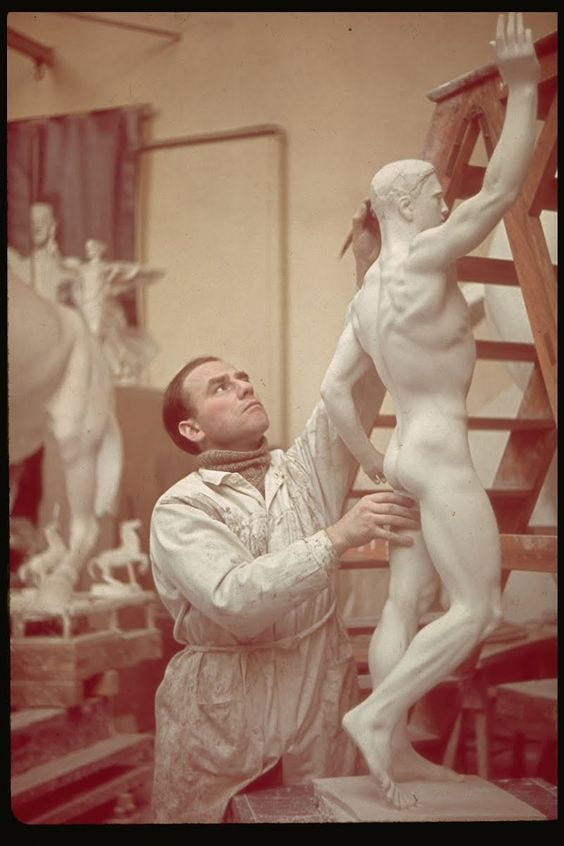

Hitler would eventually put Breker on a list of 378 deemed ‘divinely gifted’ in art, and thus exempt from military duty. Alongside Breker was fellow sculpture Josef Thorak. Early on, Thorak was hailed by Rosenberg and Goebbels as one of Germany’s greatest talents, and over time Breker too would earn a similar level of respect. Both of these artists would become the ‘official sculptors’ of the Reich, receiving many commissions, and working as a professor in Berlin during the war.

After the war, Breker would face several setbacks. Despite never adopting the ideological beliefs of the Nazis, his association as a commissioned artist led to his dismissal from official positions. At one point, however, he was offered a job by Josef Stalin, to which he responded that ‘one dictatorship is sufficient for me’. In the new western Germany, Breker would return to Dusseldorf, with occasional trips to Paris. Thanks to his training decades earlier, he was able to find professional work as an architect, which would remain his primary occupation for many years. He would however continue sculpting on the side. Thanks to his popularity as a talented sculptor, he would once again receive many commissions, with a keen skill at crafting unique and detailed portraits, which he would do for a variety of well-known politicians, artists, and cultural icons. He continued this work until his passing in 1991, at the age of 90.

INFLUENCES

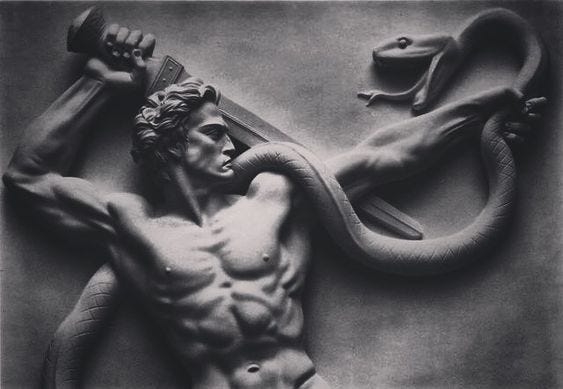

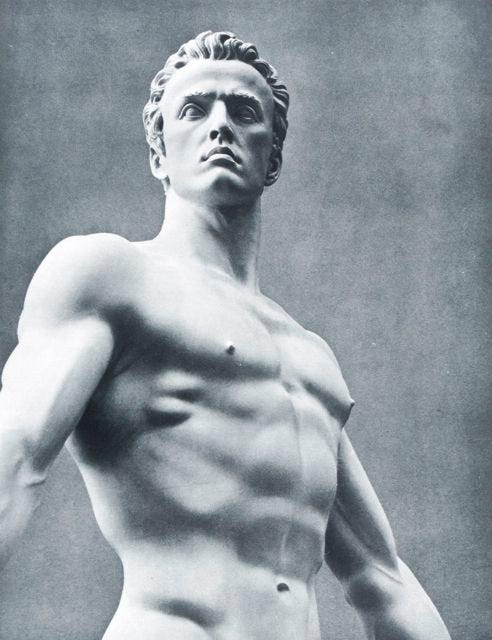

Arno Breker’s style is easy to identify, an obvious talent making it no surprise that he won his pre-war commissions. Much of his aesthetic revolves around a militaristic heroism, drawing on popularised images of the ancient Germanic or Greek gods and heroes. What stands out about his sculptures is the timeless nature of his figures which seem to avoid being cast into any particular time period. Without detailed armour or external detail, his figures stand alone, sometimes with weapon in hand, suggesting that his works are portraying some type of eternal truth or concept. This was likely one of the driving factors behind his success, as many - including the Reich and later Stalin - all saw potential in him to create inspiring images to which a population could rally.

Today, Breker’s style is often remembered as neoclassical. In recent years, however, some have claimed that his art expresses a melodramatic tension more akin to the 16th century reaction to the classical and idealised naturalism known as mannerism. His art does attempt to idealise and exaggerate (or amplify) the qualities being represented. Whether or not this is true is a matter of debate, as it can also be argued that his works were not necessarily exaggerations, but rather idealisations to the highest degree. Nevertheless, it seem that one of his most significant inspirational figures was Michelangelo. And this would become one of the primary points of critique for his work. The likeness between Breker’s work and Michelangelo’s is strong, however many claim that Breker lacks a level of specificity, which is necessary to display complex human emotions, resulting in statues which exude a type of anger. It is difficult to know if Breker intended this or not, however, when comparing the artists, it is evident that Michelangelo’s work is indeed more advanced in the portrayal of facial expressions. Nevertheless, Breker was described by French sculptor Aristide Maillol as ‘Germany’s Michelangelo’.

CONCLUSION

Today, because of his former position as a Nazi sculptor, Breker remains a controversial yet respected figure. His work, however, stands quite apart from the Nazi regime and no doubt he would have risen to prominence regardless of the controversies of the war. In the same tradition of great classical and neoclassical works that inspired him, Breker’s art boasts the same timelessness and emotional power – very different to the abstract expressionism in vogue by his contemporaries. His life was dedicated to the beautiful, considered by Nietzsche to be the highest virtue of all. French art historian, Dominique Egret, says of Breker that he was “Badly treated by history, when at the age of 45 he stood at the height of his creative power, it was only by dint of his astounding will-power and faith that he was able to carry on without deviating from his moral and aesthetic principles, although a large part of the work which had until then escaped the air raids, was now thoroughly and systematically destroyed.”

Thankfully there are now some who will evaluate and judge the entire oeuvre of one of the most significant sculptors of the twentieth century on the grounds of his work rather than the circumstances of world war two.

Like History Documentaries? Support our sponsor, History Fix. To get 30% discount on the first year of an annual subscription, use the code 30PERCENTOFF

Share this post