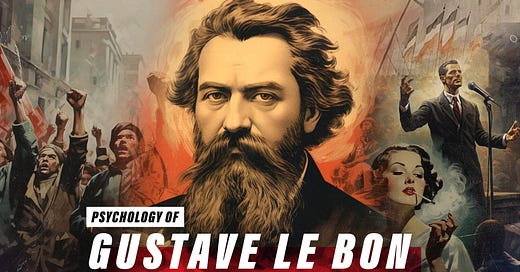

French polymath, Gustave Le Bon, a social psychologist born in 1841, stands out as the most influential thinker on crowd psychology. His book "The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind", would become foundational for 20th Century propaganda – from selling cigarettes to American women to mobilising masses to commit acts of genocide.

Gustave Le Bon

During the 19th Century various thinkers studied and wrote about the behaviour of crowds. Scottish journalist and writer, Charles Mackay, wrote “Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds" in 1841 – exploring the history of mass hysteria, manias, crowd behavior and the psychology of collective actions. French sociologist, Gabriel Tarde, explored imitation and the shaping of individual behaviour in the group setting in his book “The Laws of Imitation”, written in 1890. And into the early 20th Century British-American psychologist William McDougall wrote “The Group Mind” in 1920, about the influence of groups on the individual. But it is a French polymath who stands out as the most influential thinker on crowd psychology. Gustave Le Bon, a social psychologist born in 1841, is famously known for his book "The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind". This work would become foundational for 20th Century propaganda, from selling cigarettes to American women to mobilising masses to commit acts of genocide.

Le Bon came from a family of prosperous landowners, was well educated, and develop a keen interest in a wide range of subjects, including medicine, anthropology, physics, and psychology. He earned a medical degree in 1866 and a doctorate in 1886. His early career included medical practice, exploration, and scientific research.

However, Le Bon is best known for his pioneering work in the field of social psychology, and how an individuals' behavior changes when part of a collective group. He argued that when individuals join a crowd, they often lose their rationality and can become irrational and prone to suggestibility, often leading to destructive or impulsive behavior. His writings had a profound impact on the understanding of group psychology and collective behavior.

There are around half a dozen characteristics that Le Bon identified as unique to crowd behaviour. Firstly, individuals in a crowd tend to feel a sense of anonymity, which diminishes their sense of personal responsibility for their actions. This anonymity can lead to a decreased fear of social consequences and a willingness to engage in behaviors they might not consider when alone. Le Bon wrote that "An individual in a crowd is a grain of sand amid other grains of sand, which the wind stirs up at will."

Le Bon also observed that in a crowd, individuals become highly suggestible, meaning they are easily influenced by the emotions and opinions of others. This heightened suggestibility can lead to rapid and extreme shifts in behavior, as people conform to the prevailing mood of the crowd. In relation to this heightened suggestibility Le Bon wrote that "Whoever can supply them with illusions is easily their master; whoever attempts to destroy their illusions is always their victim." This, as we will see later, became a central tenant in 20th Century totalitarian propaganda strategies.

Another characteristic of crowds, according to Le Bon, is that emotions and behaviors can spread rapidly within a crowd. Such a contagion can lead to mob behavior, riots, or other forms of collective action. Such action can be irrational as the crowd can lose the capacity for critical judgment, driven rather by instincts and emotions over logic and level-headedness. Le Bon wrote, rather pessimistically, that "Crowds are always unconscious, and in consequence always barbaric."

Crowds also tend to exhibit a certain level of homogeneity, as individuals in a crowd often conform to the dominant beliefs and behaviors of the group. The sense of unity within a crowd can also lead to intolerance and hostility toward outsiders or non-conformists. Le Bon also recognized that crowds often require strong leaders or agitators who can shape their collective will. These leaders, who may possess charisma and a talent for rhetoric, can guide the crowd's actions and emotions. Le Bon describes such leaders as “men of action” rather than just words. This characteristic of strong leadership, again, will be capitalised in the propaganda of the 20th Century to great effect.

The individual can be lost in the crowd, their sense of self merged with the group, releasing them from the usual constraints of the individual. Acts of heroism, self-sacrifice, even violence or cruelty can be at the command of the strong, sometimes worshiped, leader of a crowd. Le Bon wrote that "A crowd may easily inspire enthusiasm, but it is just as easily stirred to hatred. Heroism runs in heredity in crowds; they have a great tendency towards hero-worship."

The propagandists of the 20th Century would use the observations of Le Bon to influence the masses for their own ends. Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda in Nazi Germany, is a case in point. And Hitler himself drew upon some of Le Bon's ideas, particularly those related to crowd psychology and mass manipulation, to shape his political strategies and the propaganda machine of the Nazi regime. Hitler and Goebbels lent heavily on psychological techniques inspired by Le Bon to gain and maintain support from the German population for the Nazi cause.

Using emotionally charged messages, Goebbels and Hitler could move their audiences to a sense of urgency. Strong emotions of national pride, fear, anger, could be used to stir up a crowd to take action in support of the cause. The power of emotions to influence public opinion was at the core of the Nazi propaganda program.

To elicit such strong motivation for the cause, messages are simplified into easily digestible and polarised, black-and-white perceptions of reality. Individual rationality and critical thinking is lost in a crowd and complex ideas are not well-received. Le Bon wrote that "The masses have never thirsted after truth. They turn aside from evidence that is not to their taste, preferring to deify error if error seduce them." The Nazi propaganda machine also understood that crowds prefer simple ideas that are emotionally appealing, even if those ideas are not based on truth or evidence. A crowd, worked up to a frenzy, will not be swayed by appeals to rationality.

Consistent with Le Bon's idea of repetition, Goebbels ensured that Nazi propaganda messages were repeated extensively through various media, making the message familiar and persuasive. The repeatedly reinforced message embeds in the collective consciousness of the crowd, and attempts to counter that consciousness is met with great resistance.

Symbols, images, and slogans complement the repetition of the message – further reinforcing it in the collective consciousness. These visual elements can evoke strong feelings and reactions, often bypassing rational thought. The Swastika, the clenched fist, the hammer and sickle, all convey a complexity of thoughts and emotions, and to which the crowd rally around as emblems of their will and desire. These simple means of creating a sense of unity within a crowd, was exploited extensively by the Nazi regime, as was evident by the abundance of emblems on display before and during the second world war in Germany and occupied territories. Under a single banner, the crowd acknowledges common goals and shared identity.

Notes From The Past is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Le Bon noted that a charismatic and persuasive leader can play a significant, even essential role in manipulating a crowd. Goebbels, along with other Nazi propagandists, contributed to the construction of Adolf Hitler's cult of personality. Hitler, as the leader of the Nazi Party, was portrayed as the charismatic and all-powerful leader who could lead Germany to greatness. His powerful oratory skills and dramatic speeches reinforced this image of a charismatic leader. He was presented as a saviour figure who could address the fears, desires, and hopes of the German people. He was depicted as the embodiment of the nation and its destiny, and any opposition or dissent was framed as a betrayal of this unity. The regime ensured that all media and communication portrayed Hitler in a positive light, while dissenting voices were silenced.

Propagandists like Goebbels also realise the absolute imperative to exploit moments of crisis, instability, or uncertainty to gain the attention and support of the crowd. And if there is no clear and present danger, then to fabricate one, with a good deal of fear and anxiety in the narrative, with the strong leader presented as the only solution. Fear is the great motivator – nothing moves a crowd like a good dose of fear. Basic survival instincts overwhelm the intellect, and a fearful crowd will follow a perceived saviour to wherever he may lead them. It can even be that the use of selective information, half-truths, or even misinformation is acceptable if it is seen to help save the people from the crisis. The crowd’s diminished capacity for critical thinking will blindly accept such anomalies if salvation is the promised outcome.

But it was not just charismatic totalitarian leadership that learnt from Gustave Le Bon and applied his principles in the public sphere. Edward Bernays, an American theorist often referred to as the "father of public relations," was also significantly influenced by the work of Le Bon, and his understanding of group behavior.

Bernays became deeply interested in the psychology of groups and the ways in which individuals' behavior changes when they are part of a collective. Drawing upon Le Bon's insights on the suggestibility, emotional contagion, and irrationality of crowds, he developed an understanding of how to influence and manipulate public opinion. He recorded this understanding in books such as “Crystallizing Public Opinion” (1923), and “Propaganda” (1928), laying the groundwork for modern public relations techniques and the understanding of how to shape public opinion through persuasive messaging and emotional appeals. Bernays saw the potential for controlling and guiding public opinion by appealing to people's emotions and desires, in much the same way as the Nazi Party had, albeit for commercial, rather than nationalistic, ends.

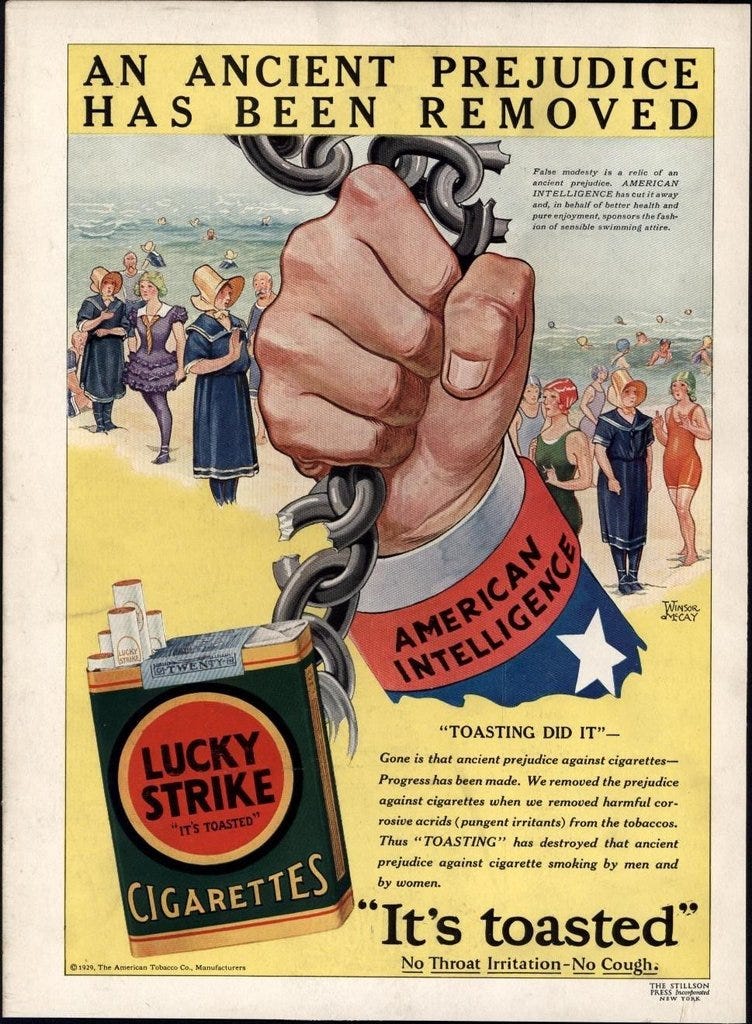

In one of the most famous campaigns orchestrated by Edward Bernays, he sought to promote smoking among women in the 1920s. At the time, it was considered taboo for women to smoke in public, and only 5% of cigarette sales were to women. Bernays was employed to do something about the situation for the tobacco companies. He cleverly linked smoking to the idea of women's liberation and used the feminist movement to his advantage. He staged a dramatic event where women, referred to as "Torches of Freedom," would light up cigarettes during the 1929 Easter Sunday Parade in New York City. This campaign effectively challenged social norms and played on the emotions and desires for empowerment and freedom.

By tapping into the emotions of liberation, freedom, and defiance, Bernays linked smoking to the existing momentum for women's rights and their struggle for equality. By framing smoking as an act of rebellion against societal norms, he harnessed the emotional power of this message to motivate women to take up smoking. By exploiting the prevailing social norm of the time, (that it was improper for women to smoke in public) the campaign amplified the oppressive nature of the norm that instilled fear and anxiety regarding women's capacity to be free. The fear of being bound by social conventions was a powerful motivator to challenge the status quo. "Torches of Freedom" were presented as powerful symbols of liberation and freedom, appealing to the idea of enlightenment and progress. Even though the aim of the campaign was to just sell cigarettes to women, a habit that would unlikely lead to true liberation and freedom.

Bernays also capitalised on the collective movement for women's rights by creating a sense of unity and identity among these women who smoked. By taking up smoking was to identify with the group who wanted more rights for women. Furthermore the campaign involved celebrities and prominent figures, including doctors and feminists, who endorsed the idea that smoking was a form of emancipation for women. By using respected authority figures, Bernays lent credibility to the message and played on the influence of trusted sources.

The power of the media was also on display in this campaign, having orchestrated a highly publicized event during the 1929 Easter Sunday Parade in New York City. Women were encouraged to light up "Torches of Freedom", while the media coverage amplified the campaign's message and created a collective experience for those who witnessed it, further reinforcing the idea of a societal shift. The lighting up of cigarettes at the event was small, carefully planned with hand-picked women paid to light up at the parade, and specific photographers to capture the moment - it was theatre, a far cry from a spontaneous situation, as it had been portrayed to the public. Nevertheless, the impression was powerfully amplified and quickly gained momentum. The purchase of cigarettes by women went from 5% in 1923 to 12% in 1929, and continuing to rise to just over 18% in 1935. With similar campaigns after World War 2, seeing the percentage of women purchasing cigarettes continue to rise. The same propaganda techniques are used, promoting smoking to women as symbols of upward mobility, gender equality and freedom.

Gustave Le Bon believed that individuals should be educated about the psychology of crowds and the effects of collective behavior on individuals. He argued that understanding the dynamics of group psychology would help people become more aware of their susceptibility to crowd influence and make them better equipped to resist manipulation. He believed that education should focus on developing critical thinking skills and individual autonomy. By fostering the ability to think independently, individuals would be less prone to succumbing to groupthink and irrational behaviors when part of a crowd. Le Bon was very aware of the ethical concerns associated with his understanding of crowd behavior. He argued that education should instill a strong moral foundation and values to guide individual behavior and decision-making, particularly when those values might be challenged within a collective setting. Communities should encourage and celebrate individuality, nurture the development of individual character, and educate people to resist the conforming pressures of a crowd and maintain their moral compass.

Unfortunately, it is not the schools that are studying Le Bon to immunise the next generation from the madness of crowds, but it is the propagandists who have adopted Le Bon as their playbook.

May we all become more aware of the tactics employed by manipulators of the crowd, lest we become unwitting pawns in the hands of those who would exploit us for nefarious ends.

George Creel - Selling a War

George Creel was a progressive reformer who advocated for social and political reforms and saw the government as key in shaping public opinion and promoting social change. He saw propaganda as the primary tool to mobilize public support for such causes and this propaganda agency to release government news, sustain morale, administer voluntary press cens…

Like History Documentaries? Support our sponsor, History Fix. To get 30% discount on the first year of an annual subscription, use the code 30PERCENTOFF

Share this post