George Creel was a progressive reformer who advocated for social and political reforms and saw the government as key in shaping public opinion and promoting social change. He saw propaganda as the primary tool to mobilize public support for such causes and this propaganda agency to release government news, sustain morale, administer voluntary press censorship, and propagandize abroad. This is the story of the Committee on Public Information (CPI) and Woodrow Wilson's efforts to sell WWI to the American public.

George Creel was born December 1, 1876, to Henry and Virginia in Lafayette County, Missouri. At 19 he started his career as a journalist with the “Kansas City World”. By 23 Creel became the owner, editor and publisher of “The Independent”, a paper dealing with many social issues of the day. In late 1909 Creel gave The Independent away to two young women aspiring to be newspaper publishers and he moved on to be an editorial writer for the Denver Post, writing for Cosmopolitan, and then The Rocky Mountain News. In June 1912 Creel shifted gears and became the Police Commissioner of Denver where he launched some very ambitious reform campaigns. After being fired as Police Commissioner (for pressing the Mayor to fulfill his campaign promises), Creel moved on to politics, supporting President Woodrow Wilson’s re-election efforts, eventually to become the chairman of the Committee on Public Information, commonly referred to as the CPI. In this role Creel was to use his expertise in communication and public relations in efforts to shape public opinion in support of World War one. Creel was a progressive reformer who advocated for social and political reforms and saw the government as key in shaping public opinion and promoting social change. He saw propaganda as the primary tool to mobilize public support for such causes and this propaganda agency to release government news, sustain morale, administer voluntary press censorship, and propagandize abroad, suited him well.

Formed in April of 1917 the Committee on Public Information (CPI) was a move by President Woodrow Wilson to mobilize public opinion toward support for the war effort. This was a significant project with an estimated $10 million budget - roughly equivalent to several hundred million dollars in today's currency.

Creel's role as the head of the CPI was pivotal. His background in journalism and public relations made him well-suited to lead the committee and gather hundreds of the nation’s most talented artists and spokesmen to patriotism, fear and keen support for the war.

Creel was a dynamic and energetic leader, quick to make decisions, often impulsive, and who enthusiastically built a broad and sweeping propaganda machine to induce the ideological mobilization of an entire nation. What he euphemistically called “The House of Truth” included divisions for domestic news, foreign news, advertising, pictorial publicity, film, academia, public speaking, a national school service bulletin and a Censorship Board. In his book “How We Advertised America”, Creel reveals that,

There was no part of the Great War machinery that we did not touch, no medium of appeal that we did not employ. The printed word, the spoken word, the motion picture, the telegraph, the cable, the wireless, the poster, the sign-board – all these were used in our campaign to make our own people and all other people understand the causes that compelled America to take arms.

Borrowing from Gustave Le Bon, a French psychologist and sociologist known for his work on crowd psychology and the psychology of influence, Creel used Le Bon's ideas on mass behavior to shape the propaganda efforts during World War I, as well as gleaning from the propaganda efforts in Europe at the time.

Le Bon's work, particularly his book "The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind" (published in 1895), explored the idea that people in a crowd or group often behave differently from how they would as individuals. Emotion, suggestion, and contagion shape the behavior of crowds. Thus using the emotional nature of crowd behavior, a strong emotional appeal can heavily influence a crowd's actions. Le Bon argued that emotions, rather than rational thinking, were the driving force behind crowd psychology. Creel recognized the importance of such emotional appeals, and it became a core strategy for the CPI propaganda efforts. Tapping into emotions such as patriotism, fear, and love of country were highly effective in shaping public opinion and motivating Americans to support the war effort.

Le Bon also described the crowd psychology of suggestion and contagion. Whereby ideas and emotions could reach a tipping point and spread spontaneously and rapidly within a group. The CPI employed similar principles in its messaging, seeking to create a sense of unity and shared purpose among the American public. Creel said of the CPI’s efforts that “It was the fight for the minds of men, for the conquest of their convictions, and the battle-line ran through every home in the country”.

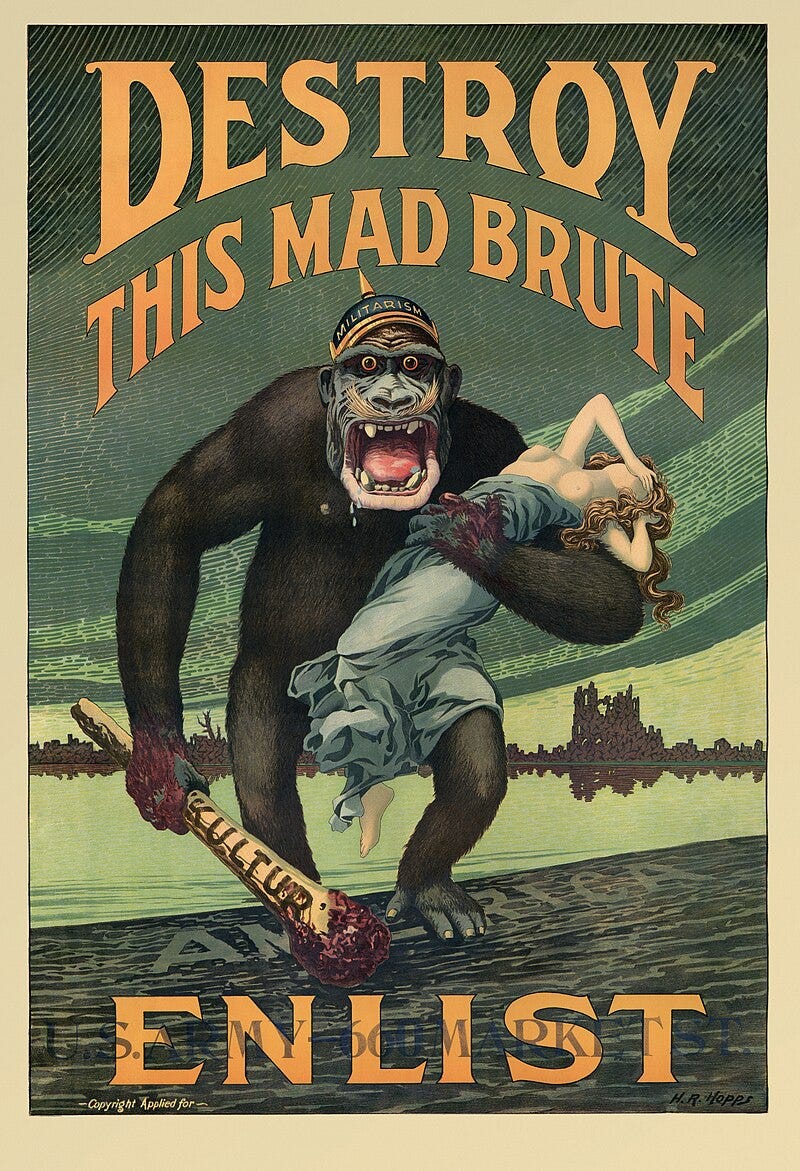

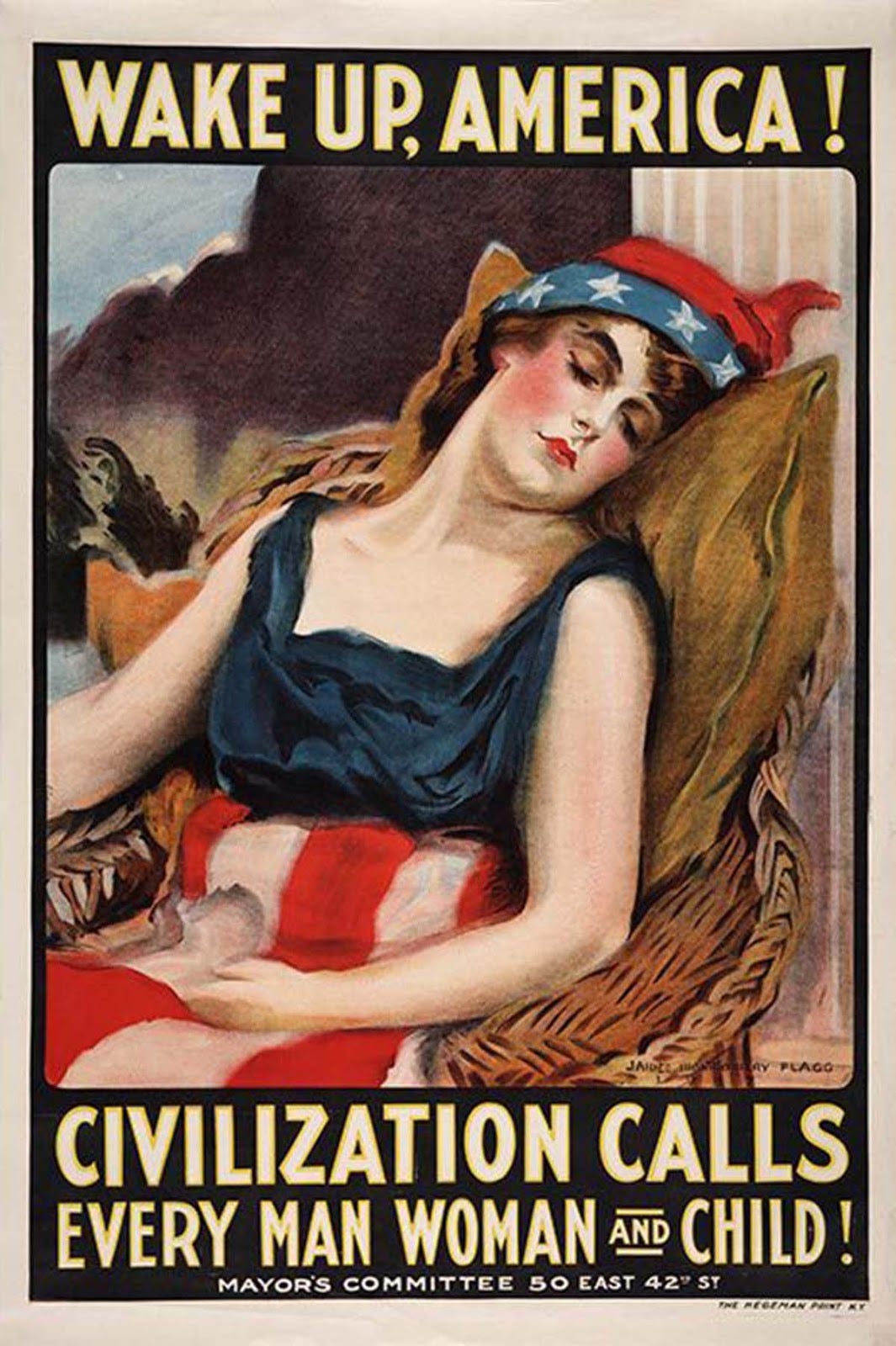

Le Bon's work also highlighted the role of visualization and symbols in influencing crowds. This visual aspect of propaganda was harnessed by the CPI in their many posters, pamphlets, cartoons, symbols, and even films, to drive home the message of shared identity and purpose. A patriotic support for the war and a demonization of the enemy were encapsulated in all CPI material. Slogans like "Hearts of Steel and Nerves of Iron" and "Food Will Win the War" motivated citizens to purchase war bonds, encourage volunteerism, and advocated for conservation efforts, such as reducing food waste.

There were, of course, dissenters to the CPI's propaganda, prompting a level of censorship and surveillance to control the narrative. The Sedition Act of 1918, passed during World War I, was used in conjunction with the Espionage Act and the CPI's influence to restrict freedom of speech, leading to arrests and prosecutions of individuals who expressed anti-war sentiments. Creel even established “snitch patrols”, who were speakers (known as the Four Minute Men) to identify and report those who held anti-war sentiment. These tactics raised concerns about the limits of government influence on public opinion and freedom of expression. Creel defended such action by declaring that "The world must be made safe for democracy. Its peace must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty. We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion." The post-war era, when it was safe to do so, saw debates about the ethical boundaries of propaganda and the role of media in shaping public perception. A debate that is as lively and relevant today as it was in Creel’s day.

But it was not just domestic propaganda entrusted to the CPI, but the importance of shaping international perception of the United States and its role in the war was also under its purview. It produced propaganda materials in multiple languages to reach a global audience, aimed at presenting the United States as a moral and just nation fighting for democracy and against authoritarianism.

Another notable American journalist and intellectual at the time of the CPI’s propaganda efforts was Walter Lippmann. His most influential work was a book titled "Public Opinion," published in 1922, influenced by his observations of the CPI's activities during the war. In this book Lippmann explored the role of propaganda and the media in shaping public perception and opinion. He argued that the public often formed opinions based on stereotypes and simplified representations crafted by propaganda, rather than through direct, informed deliberation. Of the media, Lippmann laments, “The world outside, which is only incidentally the world reported by the newspapers, is a much larger and more various world than the newsprint can convey." He criticized the CPI for simplifying complex issues and manipulating public sentiment through the control of information and the use of emotionally charged messages.

Such tactics hindered the development of a well-informed and thoughtful citizenry. However, Creel declared that "It has been our task to set forth the facts, the sober truths, the inspiration, the ideals, before the world." It is difficult to determine if Creel really believed this or if this was yet another part of the propaganda program. Lippmann’s criticism of the CPI contributed significantly to debates around the ethics of government-sponsored propaganda and its impact on democratic principles, freedom of the press, and public discourse. He believed there is a role for experts and informed leaders to guide public decision-making, but in a way that enhances individual freedoms and democracy, not railroad it. He said

"The public must be put in its place, so that it may exercise its own powers, but no less and perhaps even more, so that each of us may live free of the trampling and the roar of a bewildered herd."

Probably the most effective strategies employed by the CPI was the skilful marriage of visual and emotional appeals that resonated with the American public while nudging them toward the opinion of the government. The CPI created a wide range of visually striking materials, including posters, cartoons, and films, featuring powerful and memorable imagery. Complex issues were boiled down to a simple, yet powerfully emotional message. The iconic poster of James Montgomery Flagg's "Uncle Sam Wants You" became an instantly recognizable symbols of patriotism and recruitment. Messages were crafted to tap into strong emotions, such as fear, pride, and love of country, to motivate individuals to support the war effort. Emotional connections were forged through stirring slogans, such as "The Hun: His Mark - Blot It Out!" portraying the German enemy as a menacing, even demonic, force.

The propaganda used straightforward language and uncomplicated visuals that could be easily understood by people from diverse backgrounds and education levels. In other words, complexity reduced to the common denominator. There were no grey areas – it was black & white, and the ‘right’ sentiment was obvious. Such slogans and images were used consistently across various media to reinforce the message. Repetition branded these messages into the public's consciousness. The CPI capitalized on Americans' sense of nationalism and pride in their country. The consistent message was that the United States is a noble defender of democracy and freedom, articulated by the best writers, artists and illustrators the government could employ.

The films produced by the CPI were instrumental in conveying this message of patriotism. They were shown in theaters across the United States and, along with other CPI propaganda materials, proved very effective in shaping public opinion and maintaining support for the war effort. They were written to evoke strong emotions, demonize the enemy, and promote American involvement in the war. The propaganda was not subtle and was regarded as manipulative by some critics and members of the public at the time. While they were effective in conveying patriotic messages and rallying support for the war effort, the films also faced criticism for their obvious propaganda techniques.

Once again, the simplification of complex geopolitical issues and disregard of important facts presented a black and white, good verses evil representation of reality. Creel's willingness to prioritize the power of an idea over strict adherence to factual accuracy is encapsulated in his saying "Truth and falsehood are arbitrary terms. The force of an idea lies in its inspirational value. It matters very little if it is true or false.” The intricacies of the war and the complex motivations of nations involved were all pushed aside to present a demonic German enemy and angelic American saviour, was disingenuous at best. Some critics contended that the overly nationalistic themes promoted a blind patriotism that encouraged conformity and discouraged critical thinking.

Some of the films from that time:

"Under Four Flags" (1917): This documentary-style film aimed to demonstrate America's diverse heritage and the need for unity in times of war. It showcased various ethnic groups living in the United States and emphasized their loyalty to the country.

"America's Answer" (1918): This propaganda film highlighted the American response to the call for help from war-torn Europe. It showcased American soldiers and resources being sent overseas to aid the Allied forces, emphasizing the United States' role in bringing about victory.

"The Heart of Humanity" (1918): Directed by Allen Holubar, this film depicted the atrocities committed by the German army in Belgium and portrayed Americans as saviors and defenders of freedom. It aimed to evoke strong emotional reactions and build support for the war.

"Pershing's Crusaders" (1918): This documentary-style film celebrated General John J. Pershing and the American Expeditionary Forces' role in the war. It showcased the soldiers' training, equipment, and determination to fight for freedom.

Educational Films: In addition to narrative films, the CPI produced educational films that explained various aspects of the war, such as the causes of the conflict, the importance of buying war bonds, and the need for conservation efforts.

The CPI was disbanded shortly after World War I ended in 1919. During and after World War II, the United States established several government agencies and initiatives that were responsible for propaganda, information dissemination, and public relations efforts. These included: The Office of War Information (OWI), established to manage government information and propaganda efforts. It was responsible for coordinating the production of propaganda materials, such as posters, films, and radio broadcasts, to promote the war effort and maintain civilian morale. Like the CPI, the OWI played a crucial role in shaping public perception during the Second World War.

After World War II and during the Cold War era, the United States Information Agency (USIA) was created as a separate agency responsible for managing America's overseas information and cultural exchange programs. It played a significant role in promoting American values, countering Soviet propaganda, and influencing global opinion during the Cold War.

The Department of Defense and the State Department have also been involved in various information and public relations efforts, particularly in relation to military and foreign policy. These departments have often worked together to shape public opinion, both domestically and internationally.

The legacy of the Committee on Public Information during World War I had a significant and lasting impact on later government and private initiatives aimed at swaying public opinion. It set a precedent for government involvement in shaping public opinion during times of emergency or crisis. This influence is seen in subsequent government agencies and initiatives dedicated to public relations and information dissemination during emergencies, crises, and war, be it domestic or foreign. Today the global crises around war, climate and health have seen international efforts of propaganda and strategic communication that have fundamental roots back to the theories of Gustave Le Bon and the subsequent work of the CPI.

Important ethical questions about the boundaries of government influence on media and freedom of speech continue today. The Sedition Act of 1918, which was used in conjunction with the CPI's efforts to suppress dissent, raised the question of balance between national security and individual freedoms. The same could be said about modern public relations and advertising – where is the ethical boundary between manipulating consumer perception (and resulting behaviour) and independent critical thought? Or similarly government and non-government organisation’s global “soft power” influence on foreign public opinion. Often geopolitical situations are dumbed down, made highly emotive, and served up to the public as a black and white issue, when reality is often a lot more complex.

But have the general public lost interest in participating in complex political issues, and thereby defaulting to the opinion of the propagandist? Lippmann’s lament from 100 years ago resonates today…

"The private citizen today has come to feel rather like a deaf spectator in the back row who ought to keep his mind on the mystery on the stage but cannot quite manage to keep awake."

Share this post