Iran, historically known as Persia in the West, boasts a long history reaching back many thousands of years and hosting many kingdoms and empires. In this documentary we outline the modern period known as the Pahlavis, named after the Pahlavi dynasty, that ruled from 1925 until the Islamic Republic in 1979. This was a time of dramatic change in Iran, an American led coup, the rapid westernisation of culture and industry, and a constitutional monarchy turned dictatorship, are all part of this dramatic story.

Modern Iran, Part 1: Pahlavis Dynasty (1925-1979)

Iran, historically known as Persia in the West, boasts a long history reaching back many thousands of years and hosting many kingdoms and empires. In this documentary we outline the modern period known as the Pahlavis, named after the Pahlavi dynasty, that ruled from 1925 until the Islamic Republic in 1979. This was a time of dramatic change in Iran, an American led coup, the rapid westernisation of culture and industry, and a constitutional monarchy turned dictatorship, are all part of this dramatic story.

1925-1941

On the 31st of October, 1925, Brigadier-General Reza Khan deposed the Qajar dynasty to declare himself Shah (or king) over Iran. He had successfully pushed aside the existing Shah in a military coup on the 21st of February 1921, taking up the post of Prime Minister. By 1923 Ahmad Shah Qajar and his family were in exile and Reza Khan was formally proclaimed the new Shah. He changed his name to Pahlavis, as a nationalistic gesture drawn from a pre-Islamic Sasanian Empire. He ruled as a secular king, drawing opposition from the clergy but generally supported by the middle and upper-class of society.

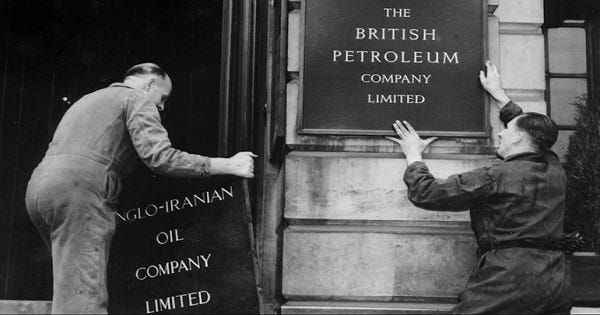

Under the former Shah, a British oil company, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC), had discovered large oil fields in Iran. By 1914 the company (51% owned by the British Government) controlled all of Iran’s oil reserves. This would prove to be a point of major contention after the second world war. Reza Shah, in 1933, had signed a completely one-sided agreement with APOC, crippling the country’s ability to profit from its own oil. It has been suggested that Iran would receive something like 16% or less of oil profits, although there was no way of knowing as the financial books were not open to the public, nor to the Iranian government.

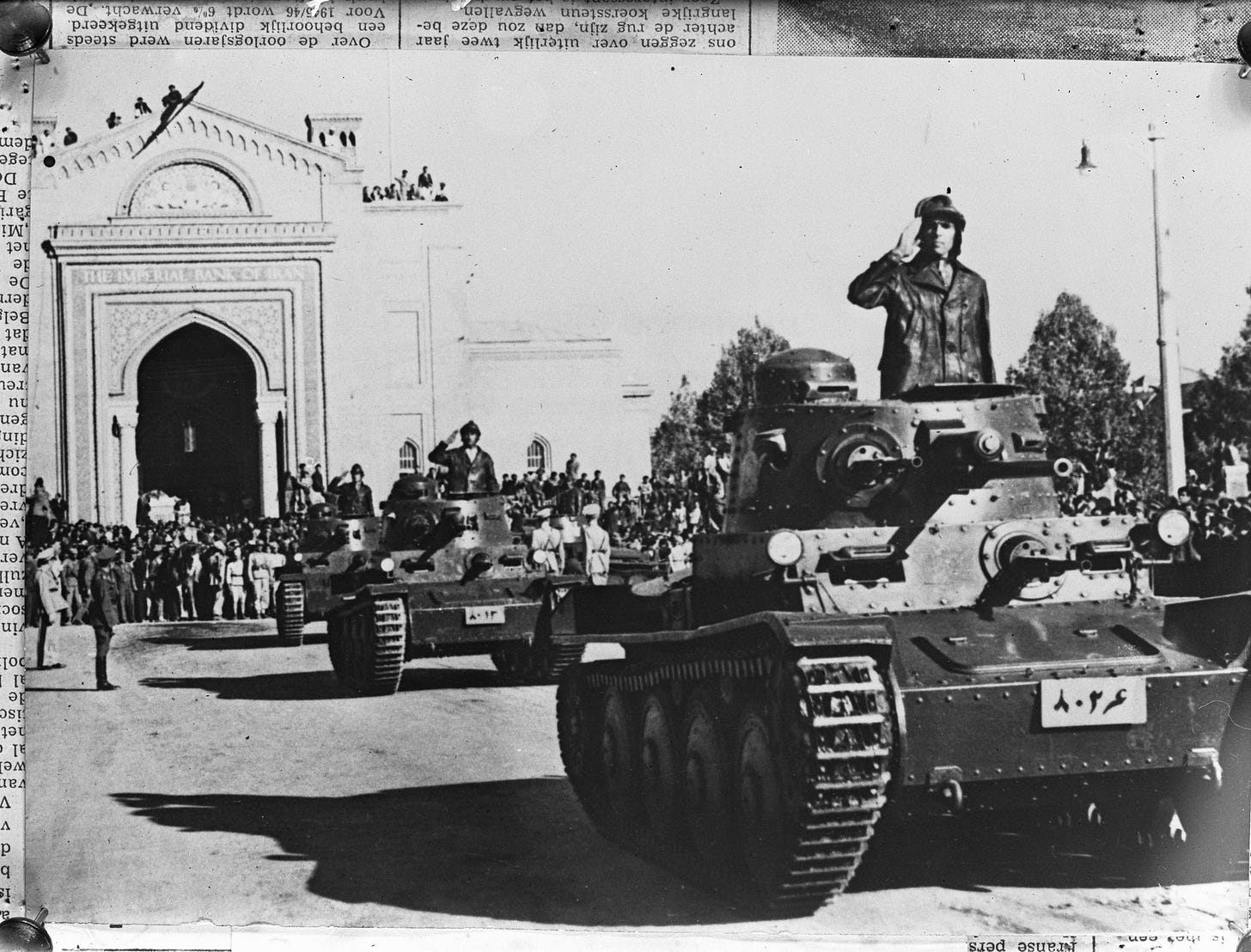

Despite British dominance in the Iranian oil industry, Reza Shah preferred technical assistance from Germany, France, Italy and other European countries. During World War 2, Britain insisted that the German engineers and technicians in Iran were spies intent on sabotaging the British oil facilities. The Shah refused British demands to expel the Germans and was subsequently labelled a Nazi sympathiser. On the 25th of August, 1941, Iran was invaded by British and Soviet forces and quickly surrendered. Under the pressures of an invasion, the Iranian military collapsed, many panicking, keen to surrender. The Shah was astounded and humiliated by his army’s collapse. By September Reza Shah had abdicated and his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, at 21-years-old, was placed on the throne.

The new Shah, also humiliated by his army’s collapse, would vow that Iran would never again be so defeated and would go on to invest billions in military spending. He would become a qualified pilot, fascinated with aircraft, and would direct more money to his Imperial Iranian Air Force than any other branch of the armed forces. During John F. Kennedy’s presidency, when Iran was seen as an important ally in the region, America was the primary supplier of military equipment.

Although the British would have rather the former Qajar family back on the throne, the new Shah would prove to be easily influenced by British and other western interests. Opposition to British interests in Iran would come from another quarter a decade later, namely from the Prime Minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh.

1941-1951

During the early 1940s, a few Soviet-sponsored local governments and the seemingly pro-Soviet Prime Minister, and the growing communist Tudeh Party, alarmed the Shah. By 1946 the Red Army had pulled out of Iran and the Shah successfully squashed Soviet puppet states in Iranian Azerbaijan and Kurdistan.

On 4 February 1949, when attending an annual ceremony at Tehran University, Fakhr-Arai fired five shots at the Shah, one bullet grazing his cheek. The would-be assassin was immediately shot by officers nearby in what was thought to be an attack by the Tudeh Party. Later evidence showed that Fakhr-Arai was an Islamic fundamentalist. Emboldened by public sympathies for his injuries, the Shah became more active in politics, using the constitution to increase his power. Mohammad Mosaddegh, a nationalist, who considered the Shah’s grab for power undemocratic, formed a coalition known as the National Front with the aim of greater liberal democracy for the country.

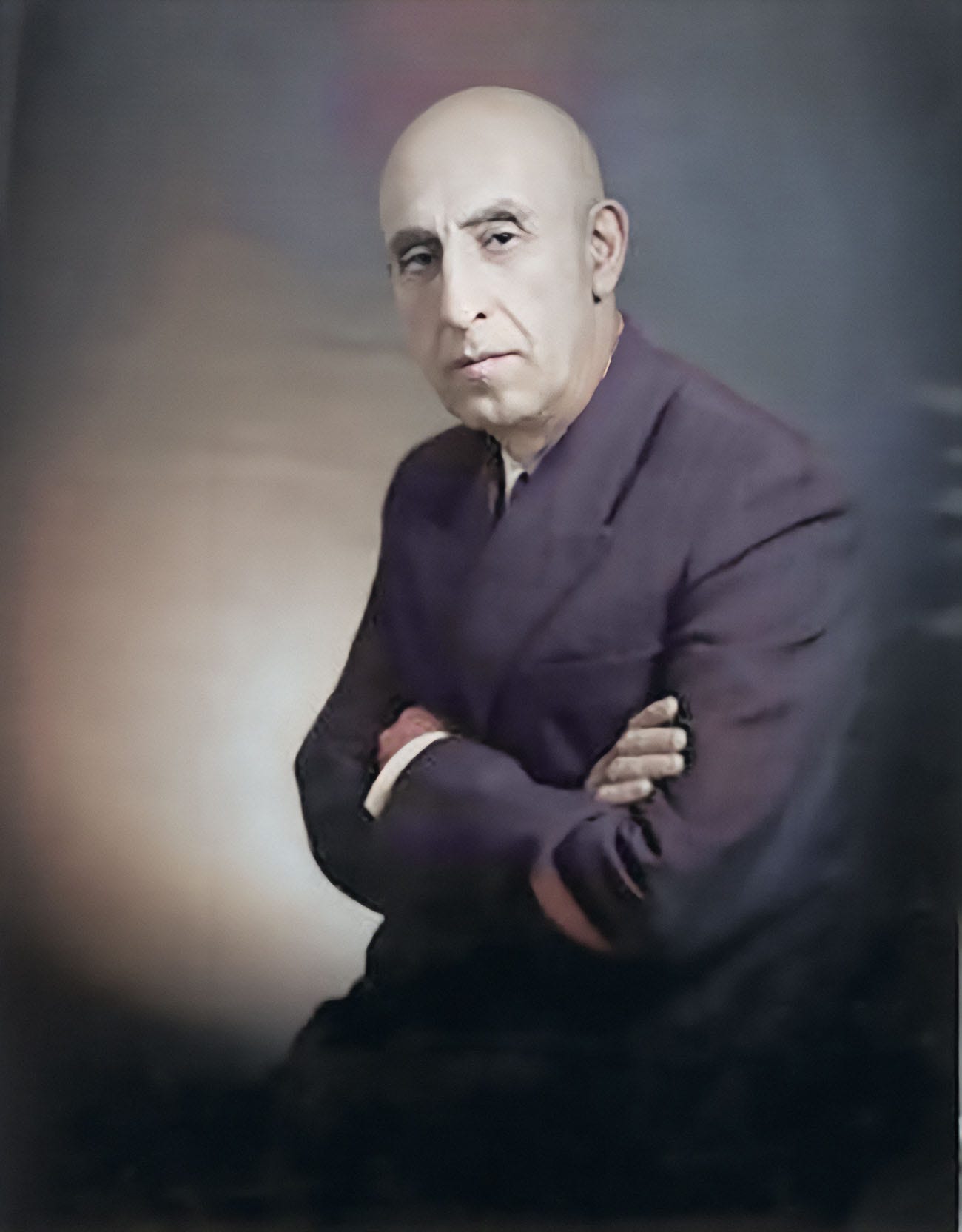

1951-1953 Mohammad Mosaddegh

Mohammad Mosaddegh was elected as the 35th Prime Minister of Iran in 1951. He had been a vocal opponent of British control over Iran’s oil, and the most significant policy of his government would be the nationalisation of the Iranian oil industry. With a nationalist sentiment sweeping over the country, Mosaddegh’s moves for national sovereignty and a liberal democracy for Iran incited demonstrations from foreign actors representing foreign interests. Nevertheless, he expropriated Anglo-Iranian Oil Company assets and nationalised the operation, with the claim that Iran was the rightful owner of all the oil in Iran. And Iran could indeed use the revenue to meet their budget as well as release them from British control and what was perceived as corruption of the country’s internal affairs.

For the British, the idea that a third world country would dictate terms of oil production to them was simply unacceptable and would do everything in its power to hinder the move. For the Americans also, this was a critical situation, as they too did not want other countries in the Middle East thinking they could re-negotiate, or dictate, terms to American companies. Considering the oil stolen, the British pulled out all its employees, closed down installations and enforced a blockade and embargo on any shipping that was going to take Iranian oil to the world market. This brought the Iranian oil industry to a standstill, while the British simply increased production in other countries such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Iraq.

In a series of legal disputes, Britain appealed to the UN Security Council to regain control of Iranian oil. In response, Mosaddegh personally went to the Council in New York to plead Iran’s case for sovereignty regarding their oil reserves. The UN Security Council refused to pass the resolution proposed by Britain. Undeterred however, Britain then took Mosaddegh to the international court in the Hague over the same matter.

Out of options, Winston Churchill appealed to American President Truman, asking for help to overthrow Mosaddegh. However, Truman was opposed to any such coup and refused to help – the British would have to wait for a more favourable administration. This opportunity came in November 1952 when Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected president.

The new secretary of state, John Dulles, and his brother, CIA director Allen Dulles, conspired with the British to overthrow Mosaddegh. They would engineer a coup d’état, under the false premise that Mosaddegh was a communist, (or, at the very least, there were communist dangers in Iran) that required the overthrow of the current government to secure the state, especially from the Soviets to the north.

1953 Coup d’état

By 1953 Mosaddegh’s popularity was waning as the British embargo on Iranian oil and political turmoils took their toll on the government. Grasping for support Mosaddegh started to rely on emergency powers to rule, with accusations that he was becoming a dictator. This was the moment for a CIA organised coup against Mosaddegh, and Kermit Roosevelt Junior was the man to lead Operation Ajax. The CIA bribed tribal leaders, clerics, military officers, newspapers editors, and members of parliament, to make claims that Mosaddegh was a dictator and accusing him of all manner of evil.

To further destabilise the government, Roosevelt wanted to give the impression that Teheran was in chaos, by organising street violence. By bribing the leader of the protection racket in Tehran – Shaban Jafari (often known as Shaban the Brainless) – The CIA effectively hired a violent mob to riot through the streets of Tehran. (Although Shaban Jafari denies that he was personally involved in these riots, claiming he was in prison at the time). With the mob shouting, “up with communism, we love Mosaddegh”, they would be countered by another hired mob attacking the feigning ‘pro-communist, pro-Mosaddegh’ rioters, thus causing absolute chaos in the streets.

Roosevelt’s plan was (under this increasing chaos and pressure) for the Shah to issue two orders – the first dismissing Mosaddegh as prime minister and the second, to name General Zahadi as the new Prime Minister.

On Saturday 15 August 1953, these orders were taken to Mosaddegh by the commander of the Imperial Guard. Mosaddegh, however, rejected the orders, saying, that they were illegal, the Shah cannot fire a Prime Minister and install another without the approval of the parliament (which was in fact incorrect – the Shah did have this constitutional right at the time). With the expectation that Mosaddegh would not concede, the plan was then to arrest him. However, Mosaddegh had been made aware of the plan and the Shah’s troops who came to arrest him were outnumbered by Mosaddegh loyal troops. Colonel Nematollah Nassiri and his Imperial Guard troops were arrested, and on the radio the next morning it was announced that a British plot to overthrow the government had failed.

That same day the Shah fled the country to Baghdad, and then onto Rome.

General Zahedi was shuttled between multiple safe houses to avoid arrest as Kermit Roosevelt regrouped the CIA for the next move. The Eisenhower administration, it seemed, was happy to leave things as they were for the time being, but some accounts suggest Roosevelt did not receive any message to cease operations and continued to organise demonstrations. Other accounts suggest that the demonstrations from this point on were not organised by Roosevelt but spontaneous. Regardless of being spontaneous or CIA-sponsored, on August 19 Tehran was again in chaos, with street violence initiated by a so-called “communist revolution” by the Tudeh party, and more mob violence courtesy Shaban Jafari’s men and others. Masses of people, fed up with the chaos, flooded the streets of the city in demonstration.

Loy Henderson, the US Ambassador, said to Mosaddegh to clear the streets and regain law-and-order or the US would not recognise him as prime minister. Mosaddegh ordered his supporters off the streets and established marshal law. This, however, gave the plot leaders opportunity to move in – under the authority of General Zahedi, tanks rolled into Tehran to arrest Mosaddegh. There was a siege at Mosaddegh’s residence and overwhelmed, Mosaddegh and his staff and household fled.

By the end of the day Zahedi and his army were in control of the government and the coup was complete.

The Shah, residing in Italy, received word of the successful coup was successful, upon which he declared “I knew they loved me.” There was a purge of all military officers deemed loyal to the former democratic government and Mosaddegh was tried in a military court on trumped up charges of treason. Zahedi was paid five million dollars by the CIA and the oil industry was de-nationalised and an international consortium was formed with 40% of the shares going to American companies. Profits were split 50/50 with Iran but the British retained overall control and renamed its oil company British Petroleum, or BP. The western war with Iranian nationalism was over, and for a time, foreign powers once again had a handle on Iran.

Before 1953 the Iranian view of America was a very positive one, however, in the aftermath of the coup, an increasing negativity toward America grew. The sentiment was that America had violated Iranian sovereignty. This, along with growing repression and autocratic rule by the Shah, would culminate in another revolt, some twenty-five years later.

Rising Autocracy 1953-1967

In 1957, a domestic security and intelligence service was established – the “Bureau for Intelligence and Security of the State”, known by the acronym SAVAK. This was the Shah’s secret police. The intelligence organisation had been in the making since the 1953 coup d’état, under the tutelage of the CIA. SAVAK had enormous powers to censor media, capture, interrogate and torture suspected dissidents. The ruthlessness and brutality of the SAVAK’s interrogation techniques instilled great fear in the population. The Shah used this agency to silence or eliminate opposition to great effect.

In 1963 the Shah introduces the White Revolution, a series of reforms to modernize Iran, improve the conditions of the people, and make Iran an economic powerhouse. Abolishing feudalism, redistributing wealth to the working class, improving education, privatisation of state own companies, women’s rights and massive urbanisation and modernisation of the country were among the key reforms. Major investments in infrastructure created considerable economic growth and in conjunction with a sizeable military build-up, established Iran as a major geo-political power in the region. The per capita income for Iranians increased greatly, literacy rates were raised from 26 to 42 percent, and women gained the right to vote, run for office, serve as lawyers and even judges.

However, not everyone was celebrating the White Revolution. Ruhollah Khomeini opposed what he considered the Westernisation of Iran and a threat to the Islamic world view. Khomeini became an outspoken critic of the Shah, especially of the Shah’s harsh treatment of his opposition by the SAVAK. After a particularly angry speech attacking the Shah as a “wretched miserable man”, Khomeini was arrested and exiled to Iraq, where he would devote 14 years developing his thoughts on an Islamic state.

King of Kings 1967-1979

It was from the mid 1950s that the Shah had started to model himself after Cyrus the Great, Persia’s most famous ancient reformer and empire builder. He was obsessed with modernising Iran and giving the Iranian people a non-Islamic identity, reflecting former Iranian Empires like that of Cyrus. In the same spirit the Shah crowns himself as Emperor (or King of Kings) and his wife Empress, in a lavish coronation on 26 October 1967. A few years later, in October 1971, the Shah celebrated 2,500 years of the Persian Empire at Persepolis. This extravagant party for world leaders was the Shah’s announcement that the greatness of Iran had returned, again referencing the ancient Achaemenid Empire of Cyrus the Great. On the last day of the celebrations the Shah inaugurated the iconic Shahyad Tower (later to be called the Azadi Tower after the 1979 revolution) which also housed a museum which contained a copy of the Cyrus Cylinder.

During the years between 1963 and 1978, Iran saw sustained economic growth, the volume of the economy increasing nearly fivefold, primarily due to the rapid growth of Iranian oil revenue. From outward appearances it seemed the Shah was achieving his dream of Iran becoming great once again.

However, the Shah was demonstrating an increasingly autocratic rule. Anyone who was thought to oppose the Shah was arrested by the Savak and imprisoned, where torture and executions were commonplace. There was no open political dialogue. The Shah became increasingly distanced from his people. In an attempt to westernise the country, the Shah ignores many elements of society, such as the traders in the bazaars, who would, for example, suffer loss when competing against western styled supermarkets. The growing discontent toward the Shah was multifaceted and growing.

In Iraq there was no such modernisation, and in exile there, Khomeini thinks deeply about how a state could be run with the Islamic clergy playing a leading role. Condemning the sensual nature of the West, he attacks the colonial powers, and preaches to a close-knit group of students thoughts of an Islamic State. These thoughts were then published as a book (the Velayate Faghih) detailing how an Islamic State could be realised. This book was initially banned in Iran – however, with the help of devoted students, the book is secretly distributed amount Iranians.

The Islamic clergy had a huge influence in Iran as they had educated the majority Shiite population. They were, amid so much rapid change in Iran, a symbol of stability for many. The Shah had renovated many mosques in the 1970s and the number of Quran schools was on the rise – the Shah was keen to show his support for the clergy despite his development programs being rooted in Western technology and values. He was, inadvertently, supporting the very forces that would destroy him before the end of the decade.

Trouble started when and article, “Iran and Red and Black Colonization”, was published that attacked Ruhollah Khomeini, calling him a homosexual, drug addict, a British spy, and not a true Iranian but an Indian. This hit piece came from the imperial Court and allegedly the Shah ordering it to be written in an insulting tone. This incited a strong reaction from Khomeini supporters and sparked nationwide protests and strikes in Iran. The Shah, now battling chronic lymphocytic leukemia, became passive and indecisive in dealing with the unrest that was picking up momentum.

On 8 September 1978, thousands had gathered in Tehran’s Jaleh Square despite the declaration of martial law the previous day. The army, showing little competence in dealing with such a situation, fired indiscriminately into the crowd, killing 64 people in the square and another 24 in clashes with martial law forces in other parts of the city. This would become known as Black Friday and marked a significant inflection point for the revolution. A general strike ensued, paralysing the country. More than 10% of the country were out in the streets demonstrating by October, with oil workers on strike the regime was on the brink of economic disaster. On the 5th of November the Shah made a televised plea to the country, announcing, “I have heard the voice of your revolution” and promised to enact reforms to ensure a corrupt-free democratic government. But it was too late. In December the presidents of the US and France, the Chancellor of West Germany and the Prime Minister of the UK were meeting to discuss the crisis in Iran. The Shah interpreted this as Western powers about to abandon him. On 16 January 1979, he left Iran to the Prime Minister Shapour Bakhtiar and left the country. The reign of the King of Kings was at an end.

Two weeks later Khomeini, who had been living in France, flies into Teheran where millions of people welcome him home after 14 years in exile. With the support of the masses Khomeini sets up his own interim government, appointing Mehdi Bazargan as prime minister, and by the 11th of February the monarchy was completely dissolved and virtually all signs of the Pahlavi dynasty were destroyed.

Now a new epoch in Iran’s long history begins – the theocratic Islamic Republic of Iran.

Share this post