Today, the term liberalism is very broad, referring to countless numbers of ideas within differing contexts. However, the term ‘liberal’ - when used by a westerner - is often referring to the apparent doctrines which underlie American culture and society. Progressive leftists will gravitate toward newer forms of liberalism, or neo-liberalism, which often have a utopian vision. More radical leftist (such as the Marxists) can also fall under the category of ‘neo-liberal’, although a distinction should be made between the highly ideological New Left, and the progressive members of the old left. A pivotal moment came in the 1960s, when neo-Marxist thinkers such as Herbert Marcuse and his followers adopted such labels as the ‘New Left’ or the ‘New Liberals’, and did away with tainted labels such as Marxist, or Communist.

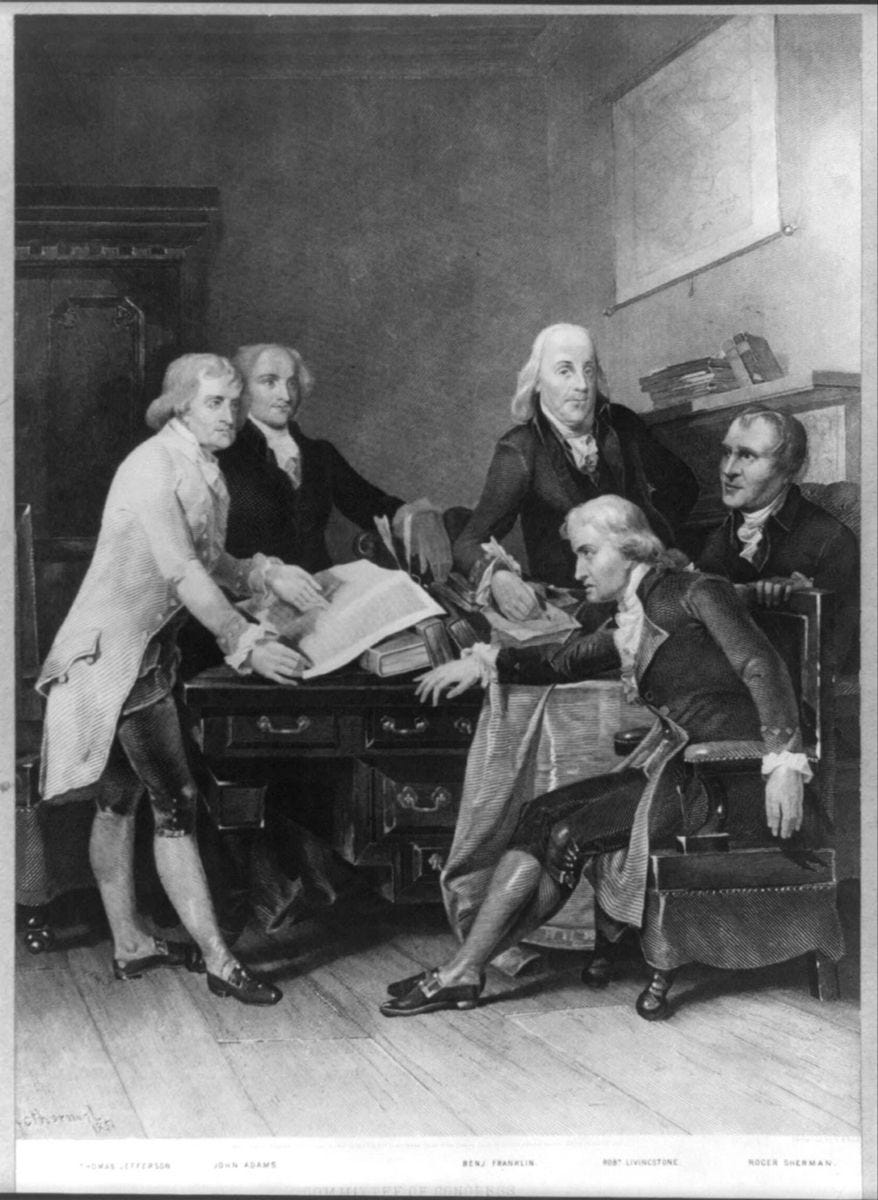

More conservative Leftists and Centrists, on the other hand, tend to believe in what they call ‘Classical Liberalism’. This is, put simply, the view that everyone holds equal value, including their opinions, and that every individual should be allowed to pursue whatever they desire, so long as it does not conflict with the law. Some Classical Liberals will reject the neo-liberal view on the necessity of state intervention and control of markets, taxation, and such. These Classical liberals with more conservative economic views (yet retain liberal social views) are often considered part of what is known as American Libertarianism. Regardless of these differences, classical liberals often hold that their form of liberalism dates to the founding fathers.

Yet despite the name, this type of liberalism is not classically American, and only emerged in the country about a century ago. To understand the differences in liberal beliefs, it is necessary to understand two important events; the American Revolution and founding in 1776, and the French Revolution in 1790.

THE REVOLUTIONS

After revolutionary victory against the British, the American founders continued in a good deal of English tradition. This included the English view on a liberal society. It was indeed far less restrictive in many ways to older forms of governance and social orientation, which some at the time viewed as negatively. However, this liberal society did not promote the idea that anything goes. Its specifics were clarified in the founding documents of the nation, most prominently in the idea of unalienable rights and sacred value of the individual. These concepts challenged competing ideas of kings and godlike rulers, since no man could act as God over any other. The liberal view was not without controversy, and some traditionalists like Thomas Hobbes held that a monarchy was a more stable form of government. Nevertheless, the promise of liberalism was satisfactory enough for the American people. Under it, individuals, who had been given equal and natural rights by their creator, would have their rights preserved along with - as it was famously stated – “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”.

Liberty was thus at the very core of establishing American society. At the time, liberty did indeed mean freedom, in so much as we have social freedom. There were, of course, logical limitations, as liberty was often viewed as the right for one to use God given abilities to pursue virtuous things. It was not unhinged from any virtue or morality. In this regard, John Adams famously said that the only ones deserving to inherit America are “a religious and moral people”. Some say that Adams himself had no real faith, yet this would further highlight his point; liberty required morals which were seen as objective - regardless of whether one had a faith in God or not.

Yet this view on liberty would quickly give way to a corrosive concept bearing the same name.

Shortly after the American revolution came the French revolution. Many in France claimed that this was inspired by the American revolution, in the pursuit of liberty. However, the French revolutionaries’ view on liberty was far different to the Americans. After securing victory, the French enthusiastically removed what they saw as the old, limiting values of the past to make way for a new society built on liberty. But this was a different take on liberty. In stark contrast to liberty in America, the French revolutionaries held that liberty was the freedom to pursue anything one desired, with no social judgement or moral imperative. Of course, not everyone held the same views, yet the most extreme forms of degeneracy and immorality were socially accepted. For example, the unhinged Marquis de Sade was elected as a representative, during which time he did nothing more than rant for long periods, mocking Jesus and talking about atheism. Sade had by this point kidnapped, bribed, or manipulated many women and even children into abuse, including torture, for his own hedonistic pleasure. This was common knowledge, yet he was still seen as an advocate of French liberty.

Notes From The Past is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In stark contrast to America, the French rejected any religious moral grounds, and would establish a state-sponsored form of atheism. This was the Cult of Reason, which took the enlightenment principle of reason and held it as a replacement for God. Thus, reason alone was the new god worthy of worship. A god that advocated for the seizure of church property by the state, for religious leaders to be subordinated under atheists, and the revolutionary spirit to be celebrated. This rather communistic cult enjoyed great success in France. A little later there was the lesser-known Cult of the Supreme Being, which held to believe in a divine god, albeit in subordination to the enlightenment principles. This, however, did not take off like the unbridled Cult of Reason. The prevailing social and economic views from this era are often identified as left libertarian in nature, although much of the French process during the revolutionary years were more like socialism.

On a side note, it is possible that the popularity of Napoleon rose from his strength of character, in stark contrast to the corrupted French politicians with their free-for-all worldview. He had Sade thrown into an insane asylum and cracked down on politicians who drove cycles of corruption - which Thomas Hobbes had warned about as he advocated for a monarchy. Napoleon also banned the atheistic cult of reason and the cult of the supreme being.

The French revolution marked what is often considered the first truly ideological chapter of the post-enlightenment period, characterised by the failing of liberal ideas to produce a strong society. That is, until it was bound under the monarch-like figure of Napoleon. The founding fathers had their own opinions on the subject. After all, America was indebted to the French for their assistance during the war of independence and were perceived as brothers in arms in the struggle against monarchy.

Thomas Jefferson was perhaps the most positive. He had lived in France during the early days of the revolution, when things seemed most hopeful. Likely assuming France would become like America, he was a strong proponent of the revolution. Returning to America, he continued to back the movement. However, as the revolution dragged on, many Americans began to see through the veneer. Wide scale unnecessary violence characterised French military units, and these reports spread across Europe and America. The execution of king Louis XVI shocked many and marked the end of most mainstream support for the movement.

Throughout this period, John Adams had been the most cynical. Even before the revolution began, Adams expressed his doubts, citing the more radical utopian ideas growing in France. By the end of the 1790s, with bodies stacking up in France, other critics such as Alexander Hamilton advocated for a move away from relations with France, and back towards England, which was more stable and less of an ideologue.

The revolution had a huge knock-on effect in Europe, particularly among the Germans who were shocked and disgusted by the revolution in France. This led to a broad rejection of enlightenment ideas in the German regions and would set the German people at odds with the French and English. Elsewhere, the prosperity of America was seen as the successes of liberty and liberalism, however the term was now also associated with the ideas of the French.

Figures such as Jefferson had subliminally pushed the idea that the French Revolution and their interpretation of liberty was basically the same as the American war of independence and American liberty. The two events were closely associated. As the decades went on, other movements began to exploit the broadening concept of liberty, with their own utopian movements. In England, the Fabian socialists - who supported such things as eugenics and state control - were often considered liberal, as were most utopian socialists. By the late 19th century, even the Marxists had become known as libertarian leftists. Of course, their liberty entailed the division of the population into people groups with different attributes, the annihilation of some of these groups, and the centralisation of the economy and society under the state. Put simply, their so-called liberty espoused in the 1890s would have been considered totalitarian tyranny by Americans living in the 1770s.

All of this would influence the 20th century view on American liberalism and liberty as a concept. In the early 20th century, liberty had indeed broadened from the freedom to pursue virtuous goals, to the freedom to pursue an increasing number of truly socially and personally destructive pathways (as long as they were within the law). Noticing this shift, in the late 1800s an increasing number of ‘anti-vice’ movements began to emerge in America. The most popular would be the movements headed by Anthony Comstock, who’s primary focus was advocating for laws that forbade the promotion of obscene or immoral ideas and products, such as pornography. As the name suggests, the anti-vice idea held that liberty was never intended to embrace the pursuit of evil vices, but rather the pursuit of virtues.

These movements did see some momentary success in suppressing certain things deemed immoral, such as sexuality obscene literature, films and images. However, the anti-vice movement eventually lost momentum to those promoting a ‘progressive’ society. By the 1950s, neo-Marxist ideas - most importantly Critical Theory - had a strong sway over America. Through the manipulation of language, the Critical Theorists were able to promote what was ultimately revolutionary Marxism, without ever using those words. Playing on keywords popular amongst the American population; namely liberalism, liberty, oppression, justice, and equality, the Critical Theorists were able to change the social landscape and forge what we see in far-left politics today.

MODERN TIMES

By the 20th Century, American Liberalism broke away from traditional morality, became an open license to pursue hedonistic pleasures, power, and indeed anything else, so long as it did not break the law.

Since the concept of liberalism was unhinged from any concept of divine virtue, it no longer held any moral constraints. And since the law was based on a moral code, it too should be liberated and free to be rewritten depending on the spirit of the times. The moral anchor has been severed from the law of the land. After all, under this type of liberty, who can say what is or is not good? There is no end to what could become acceptable within such a society.

Today, we see that liberalism - even in its so-called classical form - does not reflect the view on liberty held by the founding fathers. What is socially acceptable today are often unbound from religious morality and virtue - a state unthinkable by those who were alive during the founding of America. Today, liberty is seen as the right to publicly display one’s sexual desires, or to pursue self-destructive lifestyles, or to reject the moral code which was self-evident to the founding fathers.

Many believe that the classical or moderate liberal is merely someone that advocates for an earlier form of the corrosive belief system we see today. The question critics should be asking is not whether one is a classical or progressive liberal, but what is the definition of liberty. Is it the freedom to reject morality and take part in degeneracy, or is it the freedom to pursue virtue?

Satirist Robert Locke makes the following observation:

“If Marxism is the delusion that one can run society purely on altruism and collectivism, then libertarianism is the mirror-image delusion that one can run it purely on selfishness and individualism.”

Although Marxism and Libertarianism are not exactly mirror-images, they borrow elements from each, it is fair to note a society will not be functional based on selfish individualism, especially an individualism devoid of any moral foundation.

If we are to have a free, healthy and strong society, not one that, as James Burnham wrote, is “committing suicide”, then we should return to a liberty to pursue virtue, as was the original intent.