W. Cleon Skousen, in his book, “The Naked Communist”, paints a picture of a chilly, foggy day in 1853, when a British official stood in the rain before a hovel in London's slums. After knocking, he entered a smoke-filled room that made him cough and his eyes water. He was greeted by a barrel-chested man with dishevelled hair and a bushy beard, who spoke in a strong German accent, offered a clay pipe, and motioned him to a broken chair.

This man, Dr. Karl Marx, was a political fugitive, expelled from Germany, France, and Belgium. Now residing in England, Marx had found a base for his revolutionary work. Despite his surroundings, Marx was a university graduate with a Ph.D., and his wife was the daughter of a German aristocrat.

The officer's visit was routine, part of the British government's checks on political exiles. He found the Marxes strange but engaging, their lively conversations contrasting with the chaotic, untidy environment. In his report, the officer noted Marx's home in one of London’s worst neighbourhoods, where everything was broken and covered in dust. Yet, Marx and his wife were unembarrassed, offering warm hospitality and thoughtful conversation that compensated for their domestic disarray.

Thus, we meet one of the most dramatic figures of the nineteenth century, whose influence would grow even greater after his death. Biographers would struggle with the contradictions in Marx’s personality, calling him both a genius and a contentious, combative man, driven by turbulent forces that shaped his revolutionary life.

Karl Marx was born on May 5, 1818, in Treves, Germany. His family had a long line of scholars and rabbis, but his father broke with tradition, converting to Protestantism and becoming an attorney. This religious shift, when Marx was six, may have influenced his later rejection of religion.

In school, Marx was bright but struggled to maintain friendships due to his intensity and assertiveness. At 17, when he began university, his letters to his parents revealed a deeply sentimental side, expressing affection and emotional turmoil. However, his relationship with his father was strained, marked by frequent quarrels and financial demands from Marx.

In 1835, Marx entered the University of Bonn to study law but quickly fell into debt, joined a tavern club, and was nearly expelled for misconduct. His studies faltered, and after a duel left him wounded, he was encouraged to leave Bonn, and subsequently transferred to the University of Berlin. There, Marx’s intellectual life took shape as he pursued philosophy over law, despite his father’s wishes. He embraced materialism, rejecting the need for a Creator, and his anti-religious views were clear in his doctoral thesis, which favoured the philosophy of Epicurus and expressed disdain for the gods.

At Berlin, Marx aligned with left-wing Hegelians, who sought to dismantle Christianity. Influenced by David Strauss and Bruno Bauer, who challenged the historical validity of the Gospels, Marx considered publishing a “Journal of Atheism”, though the project never materialized. Instead, Marx found inspiration in Ludwig Feuerbach’s “Essence of Christianity”, which argued that man was the highest form of intelligence, a view Marx adopted.

Marx completed his doctorate at the University of Jena in 1841, but his ambitions to become a professor were crushed after collaborating with Bauer on a controversial pamphlet. This led to Bauer’s dismissal from the University of Bonn and Marx being barred from teaching at any German university.

Undeterred, Marx set his sights on revolution and pursued a relationship with Jenny von Westphalen, whom he married in 1843. Despite his chronic unemployment and inability to support his family, Jenny remained loyal. Marx’s life was characterized by intellectual work that rarely brought financial stability. He spent years studying and writing, often while his family struggled in poverty, relying heavily on financial support from his only close friend, Friedrich Engels. Marx never held a regular job or secured a steady income, and his financial mismanagement led to constant debt and hardship.

Biographer Otto Ruhle commented that “Regular work bored him; conventional occupation put him out of humour. Without a penny in his pocket, and with his shirt pawned, he surveyed the world with a lordly air.... Throughout his life he was hard up. He was ridiculously ineffectual in his endeavours to cope with the economic needs of his household and family; and his incapacity in monetary matters involved him in an endless series of struggles and catastrophes. He was always in debt; was incessantly being dunned by creditors.... Half his household goods were always at the pawnshop. His budget defied all attempts to set it in order. His bankruptcy was chronic. The thousands upon thousands which Engels handed over to him melted away in his fingers like snow.”

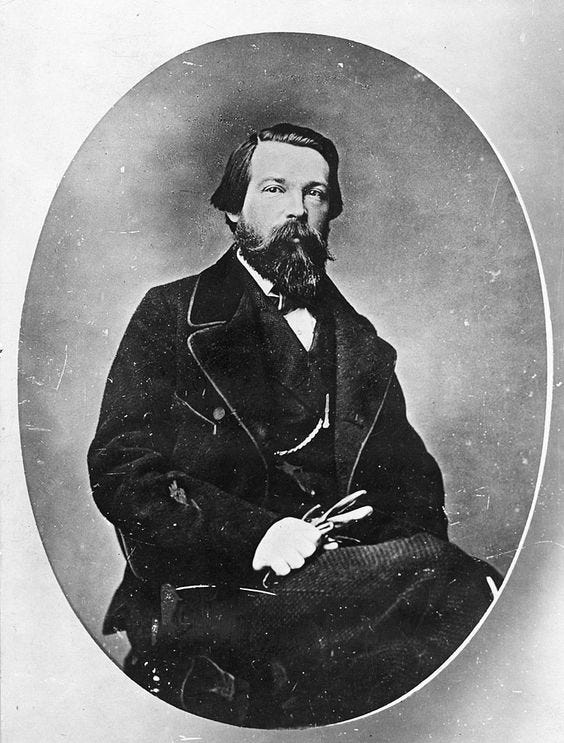

Engels was the opposite of Karl Marx in many ways. Tall, slender, and good-natured, he enjoyed athletics, liked people, and was naturally optimistic. Born in Barmen, Germany, on November 28, 1820, Engels was the son of a wealthy textile manufacturer. From a young age, he resented his father's strict discipline and the textile industry, aligning himself with the industrial proletariat.

Despite his bourgeois background, Engels had a limited formal education, lacking extensive university training. However, he made up for this with hard work and talent, mastering English and French and writing for liberal magazines in both languages.

While Engels differed from Marx in personality, both shared a similar intellectual path. Engels, like Marx, quarreled with his father, became an agnostic and cynic, and lost faith in the free-enterprise economy. He saw Communism as the only hope for the world.

Engels admired Marx long before they met. In August 1844, Engels traveled to Paris specifically to meet Marx, and the connection between them was immediate. Over ten days, Marx converted Engels from a Utopian Communist to a revolutionary, convincing him that only militant revolution, not peaceful reforms, could save humanity. Engels returned to Germany with this new conviction.

After Marx was expelled from France, Engels supported him financially, sending him money and promising more. He considered it an honour to assist Marx, seeing it as a privilege to be associated with such a genius. This partnership gave them both the courage to launch an International Communist League, advocating for violent revolution.

However, their efforts to build a revolutionary organization in France failed, as Engels found the workers uninterested in revolution. They then took control of the Workers' Educational Society in Brussels in August 1847, gaining prestige among reform organizations in Europe. This move unexpectedly positioned England, rather than the Continent, as the centre of their revolutionary activities.

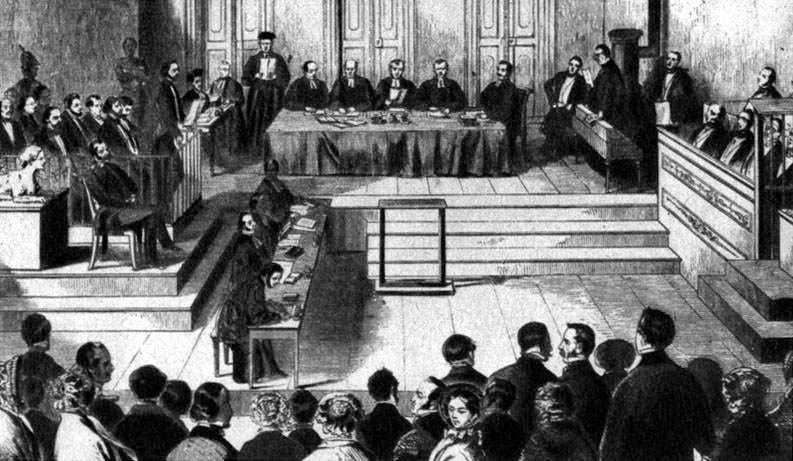

In November 1847, Marx and Engels were invited by the "Federation of the Just" (later the Communist League) to attend their second congress in London as representatives from Brussels. They took control of the congress, using strategic planning to get their views adopted. Commissioned to write a manifesto, they returned to Brussels and crafted a declaration advocating for the overthrow of capitalism, the abolition of private property and family, the elimination of classes, the overthrow of governments, and the establishment of a classless, stateless communist society. Their call to action was clear: "In short, the Communists everywhere support every revolutionary movement against existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communist revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Working men of all countries, unite!"

The revolution came sooner than expected. In February 1848, the French proletariat, joined by the resentment of the bourgeoisie, rose against Louis Philippe, leading to his ouster. A provisional government, including members of the Communist League, summoned Marx to Paris to establish international headquarters and coordinate revolutions in other countries.

However, Marx realized that launching uprisings in neighbouring countries might backfire and alienate the masses. Despite his reservations, the plan proceeded, and legions were sent to Germany. Marx followed, publishing a revolutionary paper, the Rheinische Zeitung. However, his arrogance and dismissive attitude towards differing opinions alienated potential supporters.

The German revolution, already weak, collapsed by May 16, 1849, and Marx was ordered to leave the country. He left after borrowing funds and printing the last edition of his paper in red ink, seeking refuge in France.

Upon arrival in Paris, Marx found the Communist influence had faded, and the National Assembly was controlled by monarchists. Penniless and exhausted, he fled to London, leaving his family to follow later.

Despite cramming his family into a small, slum apartment in London, Marx quickly refocused on reigniting revolutionary fervour. However, his efforts caused more division than unity, as his contentious nature led to conflicts within his ranks. Eventually, Marx alienated himself from his associates, and the Central Committee moved from his control to Cologne.

In 1852, Communist leaders in Germany were arrested and sentenced to long prison terms for their revolutionary activities. Marx worked tirelessly to help, gathering documents, recruiting witnesses, and proposing legal arguments, but all efforts failed. The guilty verdicts effectively ended the Communist League, silencing its leadership and marking its demise.

From this time onward, the Marx family lived in extreme poverty in London. Marx's letters during this period reveal a mix of deep concern for his family and a detachment as he focused on studying history, politics, and economics. Despite his wife's "nocturnal tears and lamentations," Marx was absorbed in his intellectual pursuits.

Tragedy struck the family repeatedly: in 1852, Marx's daughter Francisca died, followed by his son Edgar two years later, and another baby who died at birth two years after that.

Mrs. Marx's letters reveal her unwavering loyalty despite their dire circumstances. She describes nursing a sick child while suffering herself, and the distress when their landlady seized their belongings due to unpaid rent. With nowhere to go, and after much struggle, they eventually found help from a friend.

The Marx family's hardships are a recurring theme in Marx's correspondence with Engels, often revolving around money. Engels frequently sent small sums to support them, while Marx's letters were filled with frustration over their financial struggles.

At one point, during a particularly desperate time, Marx received 160 pounds from a wealthy uncle in Holland. Instead of using it to stabilize the family's situation, Marx spent the money on a tour of Germany, visiting friends, drinking, and indulging in leisure activities. When he returned, his wife was horrified to find that almost none of the money remained, dashing her hopes of improving their living conditions.

In 1862, a great international exhibition in London aimed to showcase industrial achievements and foster goodwill among nations. The event also provided an opportunity for British labour leaders, gaining strength since 1860, to establish an international workers' organization. They made connections with labour leaders from several countries and eventually founded a permanent "International" with headquarters in London. A key figure in this movement was Eccarius, a former associate of Marx, who invited him to participate.

Marx quickly began to assert influence, albeit with more restraint than he had shown with the Communist League. This new organization, called the International Workingmen's Association or the First International, saw Marx carefully manoeuvre behind the scenes to get his ideas adopted, even if it meant making compromises. He confessed to Engels that he included moderate phrases in the organization's rules to keep peace, even though it felt unnatural to him.

Despite his initial moderation, Marx's true intentions soon emerged. He aimed to create a core group of disciplined revolutionists and eliminate any threats to his leadership. His first target was German labour leader Herr von Schweitzer, whom Marx falsely accused of working for Bismarck, damaging Schweitzer's reputation.

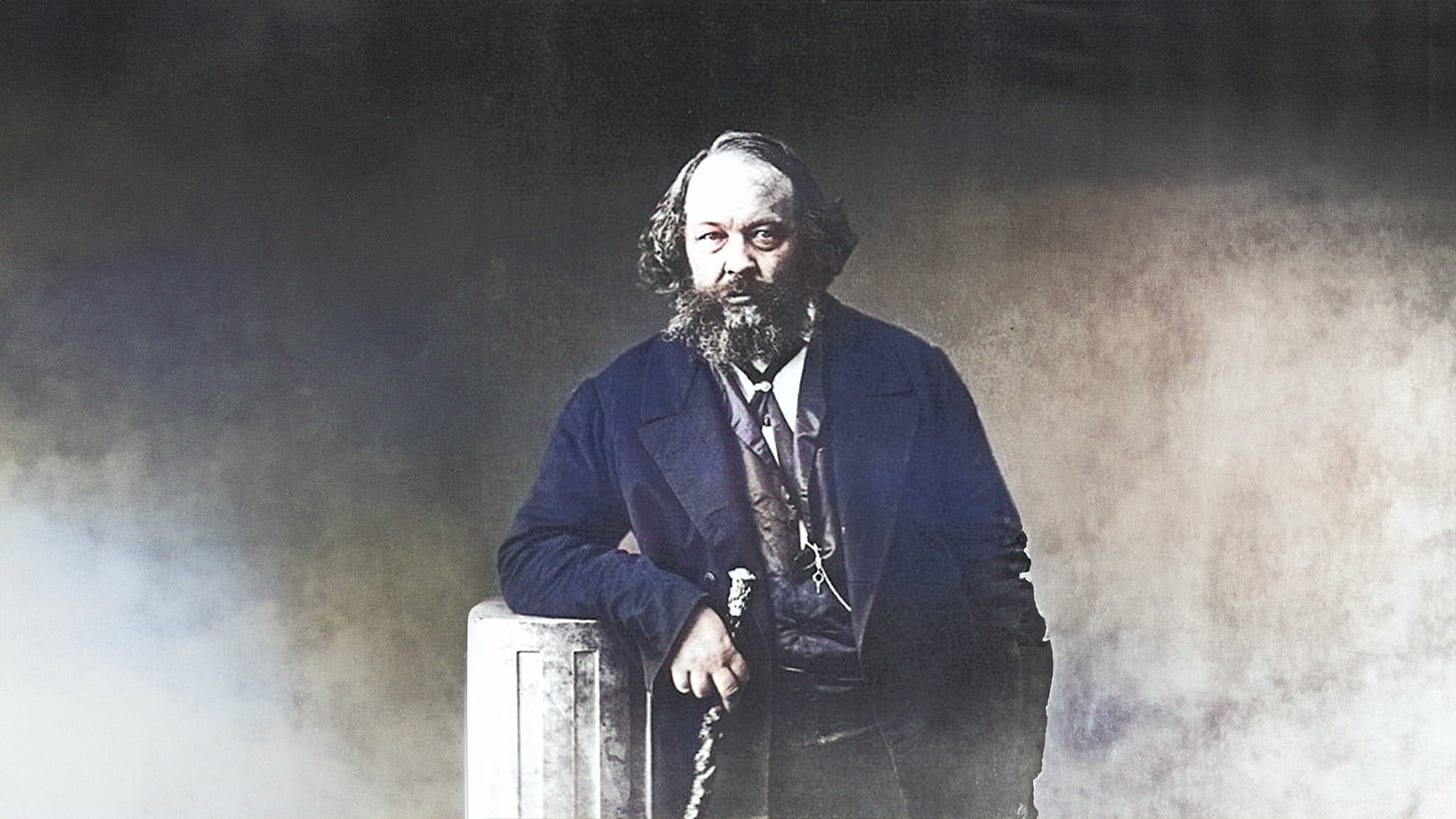

Next, Marx turned on Mikhail Bakunin, a Russian revolutionary who had become influential within the movement. Marx and Engels falsely accused Bakunin of being an agent of the Russian Czar and embezzling funds. These charges led to Bakunin's expulsion from the International, which Marx believed eliminated his last serious rival.

However, Marx's purges created distrust and dissension, leading to the disintegration of the First International. English trade unions began to withdraw, and Continental workers' groups ignored the Association's mandates. By September 8, 1873, the last congress of the International Workingmen's Association was held in Geneva, attended by only a handful of delegates. The First International was effectively dead.

Marx's drive to make the International Workingmen's Association a global movement was fuelled by his desire to implement the theories he was writing about. For years, he dedicated himself to both the International and his "book," which took a toll on his health. An old liver ailment returned, causing painful boils that plagued him for the rest of his life. In letters to Engels, Marx frequently complained about his physical suffering, even as he continued to work on his book, Capital. Despite his illness, he pushed himself to keep working, convinced that a revolution needed a solid philosophical foundation.

Marx viewed the writing of Capital as a necessary but burdensome task. He believed that a violent overthrow of the current order was justified and inevitable, and he wanted to provide a revolutionary philosophy of history, economics, and social progress. As he struggled to finalize the first volume in 1865, Marx expressed his desperation to finish, describing the book as a "nightmare." Engels, who shared in Marx’s frustration, joked about celebrating with a drink once the manuscript was completed.

Finally, in March 1867, Marx completed all revisions and travelled to Germany to publish the book. However, Capital did not achieve the immediate success that Marx and Engels had hoped for. Its complex reasoning was too difficult for the working masses and did not resonate with contemporary intellectual reformers. It would take a later generation of intellectuals to elevate Capital as a central text in their critique of the existing social order.

By 1875, Karl Marx had little to show for his years of struggle. The International had disintegrated, and his book Capital was gathering dust in bookstores. Although he continued to write two more volumes, his energy was fading. After Marx's death, Engels took on the task of publishing the second volume in 1885 and the third in 1894.

Marx's final years were marked by loneliness and defeat. He turned to his family for comfort, but his children bore the scars of their difficult upbringing. His daughter Eleanor entered a troubled relationship and eventually committed suicide, while another daughter, Laura, died in a suicide pact with her husband.

By 1878, Marx had abandoned much of his work. His confidence shattered, he was ignored by labour leaders and ridiculed by reformers. His morale hit rock bottom when his wife, Jenny, died of cancer in December 1881, followed by the sudden death of his favourite daughter, Jenny, thirteen months later. Engels noted that Marx was effectively dead after his daughter's passing. He survived her by only two months, dying alone in his chair on March 14, 1883.

Only a small group followed Marx's casket to Highgate Cemetery in London, where Engels delivered a funeral oration, offering the praise Marx never received in life.

_______

Karl Marx's life was marked by ambition, frustration, and failure. He tended to sabotage his own projects, and his writings, whether in books or letters, reveal a man whose personal struggles deeply influenced his political theories. His resentment of authority and inability to compete in a capitalist economy led him to advocate for universal revolution and a classless society.

Marx's intolerance and egotism alienated many of his followers. Bakunin, who admired Marx's intellect, calling him the supreme economic and socialist genius of the day, also described him thus:

“Marx is egotistical to the pitch of insanity.... Marx loved his own person much more than he loved his friends and apostles, and no friendship could hold water against the slightest wound to his vanity.... Marx will never forgive a slight to his person. You must worship him, make an idol of him, if he is to love you in return; you must at least fear him if he is to tolerate you. He likes to surround himself with pygmies, with lackeys and flatterers. All the same, there are some remarkable men among his intimates. In general, however, one may say that in the circle of Marx's intimates there is very little brotherly frankness, but a great deal of machination and diplomacy. There is a sort of tacit struggle and a compromise between the self-loves of the various persons concerned; and where vanity is at work there is no longer place for brotherly feeling. Everyone is on his guard, is afraid of being sacrificed, of being annihilated. Marx's circle is a sort of mutual admiration society. Marx is the chief distributor of honours, but is also the invariably perfidious and malicious, the never frank and open, inciter to the persecution of those whom he suspects, or who had the misfortune of failing to show all the veneration he expects. As soon as he has ordered a persecution there is no limit to the baseness and infamy of the method."

Despite his flaws, Marx was convinced of the infallibility of his theories, believing that historical evolution would inevitably lead to the downfall of capitalism and the rise of socialism. He preached that the proletariat had only to will this change into existence.

In his final hours, Marx had little indication that his ideas would inspire a genuine revolution. While Western Europe dismissed revolutionary violence, Russia would soon awaken to Marx's call, setting the stage for the revolution that would bring his theories to life.

Donate:

Bitcoin (BTC): bc1qytnwn0ht8p98cxs420h5kjf738unzauqd7f0rq

The Origins of Marxism in the USSR

In 1885, U.S. diplomat Andrew D. White described Russia as having "the most atrociously barbarous" government, where society was degraded, and the people crushed. At that time, Russia's population exceeded 70 million, with 46 million individuals residing in near captivity as serfs. Marx and Engels were deeply disturbed by the deplorable conditions endur…

Share this post