In 1885, U.S. diplomat Andrew D. White described Russia as having "the most atrociously barbarous" government, where society was degraded, and the people crushed. At that time, Russia's population exceeded 70 million, with 46 million individuals residing in near captivity as serfs. Marx and Engels were deeply disturbed by the deplorable conditions endured by England's industrial workers. However, it is important to note that even though their situation was far from ideal, they were still comparatively better off than the Russian peasants. The peasants in Russia faced unimaginable hardships including starvation, exploitation, and harsh political repression. The Tsar's secret police, military, and corrupt bureaucracy deprived serfs of any safeguards for their personal lives or property.

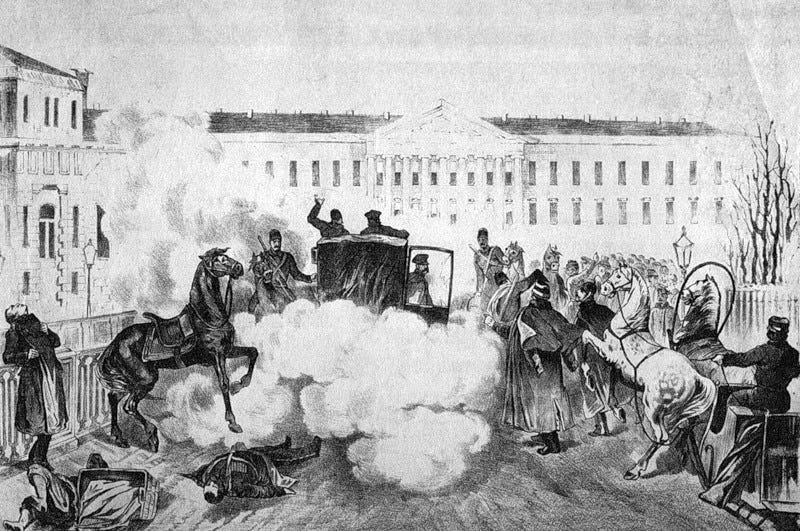

During the years 1861 to 1866, Tsar Alexander II made a bold attempt to put an end to serfdom. However, despite the Tsar's efforts, the lives of the peasants remained harsh, fuelling a growing sense of revolutionary unrest. In 1868, Marxism had made its way to Russia, thanks to Bakunin's translation of "Capital". Inspired by the fiery rhetoric of the Communist Manifesto, Russian radicals embraced the ideals of Marxism, and by 1880, these ideas had firmly established themselves in the country. In 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by a bomb, signalling to many Marxists that revolution might be imminent.

Russian Marxists questioned whether a revolution might succeed in Russia, despite the country's lack of capitalist growth, which Marx had previously seen as necessary for revolution. Upon thorough examination, Marx reached the conclusion that Russia possessed a remarkable chance to circumvent capitalism and progress directly towards revolution, marking a notable change in his theoretical position. He recognized the irony of this situation, considering his previous hostility towards Russian Marxists.

Despite Marx's criticism, Russian Marxists like Bakunin remained committed to his theories. Bakunin, even as he withdrew from public life, maintained his belief in Marxism, passing on the revolutionary mantle to a new generation. By 1876, Bakunin had passed away, leaving behind a void that would soon be filled by a new generation of leaders. Among them were Nikolai Lenin, Joseph Stalin, and Leon Trotsky, individuals who were ready to carry on Bakunin's legacy. Little did the world know that their actions would shape history, culminating in the Russian Revolution and the establishment of the world's first Communist dictatorship.

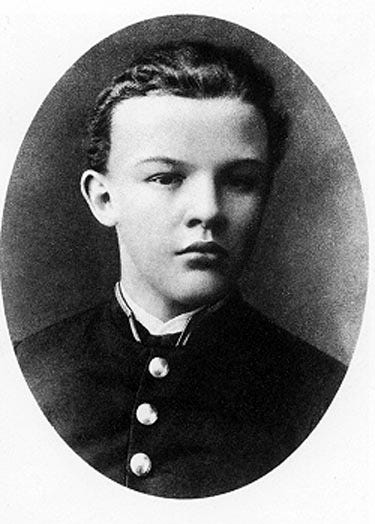

Marx likely never envisioned that the first Communist dictator would be an individual such as Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov (better known as Lenin), who was born in Simbirsk, Russia, on April 22, 1870. Lenin's father, a nobleman and Councilor of State, gained recognition for his philanthropic endeavours, having established numerous primary schools. He died when Lenin was just 15 years old. Soon after, Lenin’s older brother Alexander was executed for his involvement in a plot to assassinate Tsar Alexander III, a tragedy that profoundly influenced Lenin’s revolutionary path.

After his brother's execution, Lenin, having already abandoned his religious beliefs, immersed himself into the depths of Marxist literature, fully embracing its cynical outlook and its fervent demand for resolute action. Lenin's pursuit of law studies proved to be academically fruitful, yet his attempts to establish a prosperous legal career ultimately fell short. Amidst the devastating 1891-92 Russian famine and cholera epidemic, Tolstoy, the famous Russian writer, was organizing relief efforts, displaying his unwavering commitment to helping those in need. In stark contrast, Lenin chose to prioritize his revolutionary activities, opting not to participate in the relief efforts and was later accused of welcoming the famine as a means of inciting a revolutionary will to act among the people.

When Lenin was 23 years old, he made the decision to relocate to St. Petersburg and became a member of the "Fighting Union for the Liberation of the Working Class." Then, in 1895, he received a diagnosis of tuberculosis, leading him to seek treatment in Switzerland. It was during this time that he formed a connection with George Plekhanov, a prominent figure among the exiled Russian Marxists. Deeply moved by Lenin's unwavering passion, Plekhanov urged him to make his way back to Russia, galvanize fellow Marxists, and establish a political party rooted in the principles of Communism.

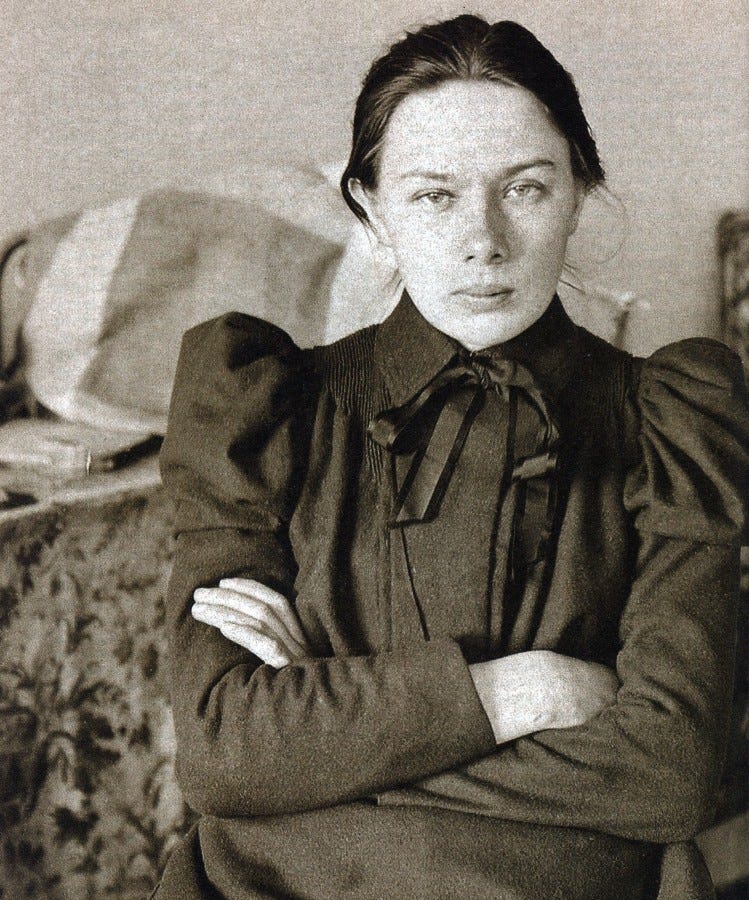

Back in Russia, Lenin engaged in revolutionary activities, but a betrayal led to his arrest and exile to Siberia. His fiancée, Nadezhda Krupskaya, joined him there, and they married to remain together, despite their Marxist opposition to traditional family structures. They chose not to have children to focus on their revolutionary ideals.

During his Siberian exile, Lenin continued to study, write, and develop the Social-Democratic Party of Russia, producing his book "Capitalism in Russia". In the year 1900, Lenin had already established himself as a seasoned and strategic revolutionary. In Munich, he made the bold decision to establish his printing press and launch "The Spark," a ground-breaking publication that would soon find its way into the hands of eager readers in Russia. This marked the beginning of 17 years of exile in Western Europe for Lenin and his wife, as they waited for the right moment to lead their revolutionary mission.

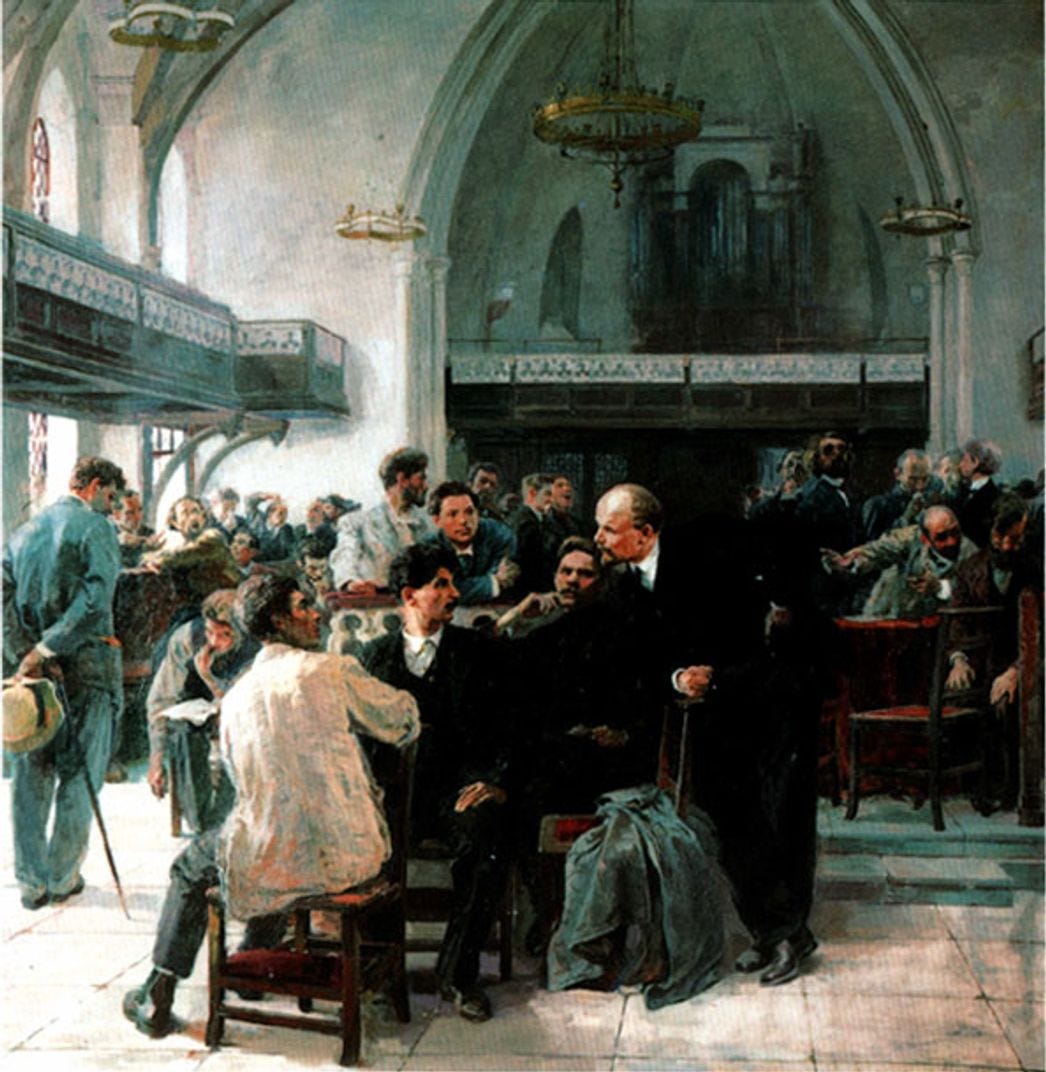

In 1903, Lenin and his wife made London their headquarters, believing they were carrying on Marx's legacy. They often visited Marx's grave, honouring his influence on their work. In July, a Russian Social-Democratic congress convened in London, attracting 43 delegates from Russia and Russian exile groups in Western Europe. Lenin, in his role as chairman, initially adopted a more measured approach. However, his concern grew as the congress started to veer towards pacifistic socialism rather than embracing the spirit of militant revolution.

In a bid to redirect the congress, Lenin rallied his followers and ignited a significant division regarding party membership. In the debate, one side advocated for a more exclusive approach, suggesting that only hard-core revolutionists should be included. On the other hand, there were those who favoured a more inclusive stance, advocating for the inclusion of sympathizers. Lenin was able to establish a temporary majority, which he cleverly used to name his faction as the "Bolsheviks," meaning "majority" in Russian. In contrast, those who opposed him were labelled as the "Mensheviks," derived from the word for "minority." This terminology served as a propaganda tool, creating the impression of broad support for the Bolsheviks, even during times when Lenin's influence was diminishing.

In spite of ultimately losing his majority at the congress, Lenin persisted in referring to his faction as the "Bolsheviks" and categorizing all opposition as "Mensheviks," demonstrating his unwavering determination to manipulate circumstances in order to further his political objectives.

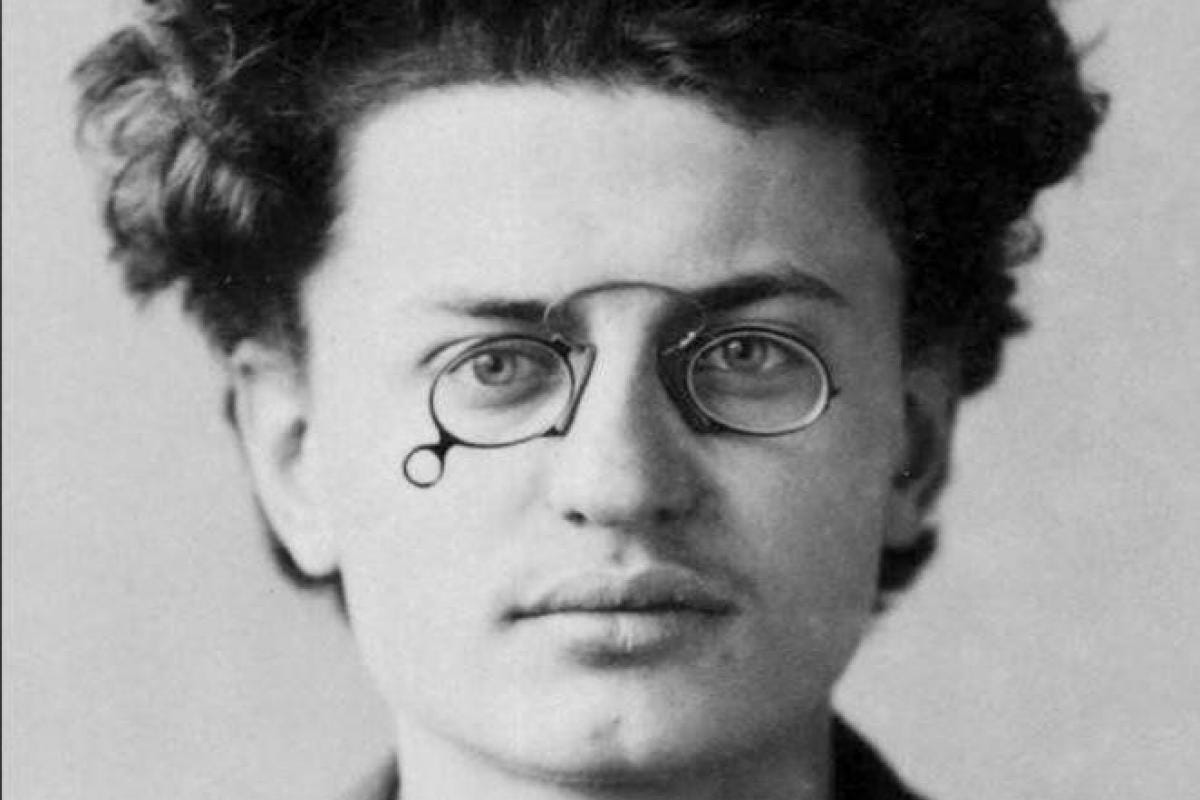

At the 1903 congress, a young and fervent individual by the name of Leon Trotsky emerged as one of Lenin's adversaries. Trotsky and Lenin found themselves on opposite sides during this congress, despite their eventual alliance. Trotsky's early life shared many similarities with Lenin's. Both individuals hailed from privileged backgrounds, received excellent educations, experienced a loss of faith, actively participated in revolutionary endeavours, and ultimately found themselves exiled to Siberia.

Born Lev Bronstein, Trotsky's father was a Kulak, or rich peasant, who had fled anti-Jewish persecution and settled in a farming district near the Black Sea. As the family's fortunes grew, they gradually moved away from religious customs, and Trotsky's father openly embraced atheism. Trotsky embraced his father's materialistic and atheistic beliefs during his time at school, evolving into a staunch materialist and political radical, much to his father's dismay. As time went on, this ideological divide caused Trotsky to become distant from his own family.

Trotsky's conversion to Marxism was influenced by Alexandra Lvovna, an older woman who taught him Marxist ideas and later became his wife. When Trotsky was just 19 years old, he and Alexandra played a crucial role in the formation of the South Russian Workers' Union. However, their efforts did not go unnoticed, and Trotsky was arrested. He spent time in solitary confinement and was eventually exiled to Siberia, where Alexandra joined him. They spent four years in a remote, barren region, where two children were born.

In 1902, Trotsky escaped Siberia by hiding in a peasant's hayload and using a fake identity—adopting the name "Trotsky" from his former jailer. Assisted by his Marxist comrades, he made his way to London and arrived just in time to participate in the Social-Democratic Congress. Alexandra and their children later joined him there.

Upon meeting, Lenin and Trotsky initially got along well, with Lenin praising Trotsky's revolutionary abilities and Trotsky supporting Lenin as chairman of the congress. Trotsky, on the other hand, quickly became concerned about Lenin's harshness, notably his chilly treatment of long-time party members who disagreed with him. In 1903, Trotsky's gentle concern for his comrades was starkly contrasted with his subsequent role, in which he supervised the brutal purges of 1917-1922.

Despite initially opposing Lenin, Trotsky's revolutionary career thrived. He emerged as a brilliant writer, a captivating public speaker, and a prominent figure in Western Europe prior to Lenin's rise. Described as handsome, arrogant, and sometimes offensive due to his taste for elegant clothes, Trotsky earned the nickname "The Young Eagle."

By 1903, Russia was on the verge of a political explosion, with Tsar Nicholas II, the final Tsar, demonstrating poor leadership. Nicholas II maintained the imperialistic and repressive policies of his predecessors, despite the initial optimism of Russian liberals. In 1903, he even led Russia into a catastrophic war with Japan. The Russo-Japanese War concluded in a humiliating defeat for Russia, which exacerbated economic and political pressures, igniting widespread unrest.

Mass demonstrations were conducted, government officials were assassinated, and a general strike was implemented, resulting in the idleness of over 2.5 million workers as Russia approached collapse. In the face of the Tsar's severe measures, such as widespread arrests, imprisonments, and even executions, the rebellion persisted, with individuals from various backgrounds rallying together in the protests. A critical event in this turmoil was the Winter Palace Massacre on January 22, 1905, also referred to as "Bloody Sunday." Father George Gapon organized thousands of unarmed laborers to peacefully petition the Tsar's Winter Palace for improved labour conditions. The Tsar, instead of engaging in dialogue with them, directed his soldiers to fire, resulting in approximately 500 fatalities and 3,000 injuries. This incident ignited a widespread revolt throughout Russia.

The Russo-Japanese War was terminated by the Tsar, who reluctantly conceded to the demands of the people outlined in the "October Manifesto." These demands included the protection of individual freedoms, the right to vote for the Duma (a people's assembly), and the repeal of any law enacted without the Duma's consent. The Tsar's realization of the gravity of the situation led him to end the war. On the other hand, Leon Trotsky viewed this as a betrayal, advocating for the total overthrow of the Tsar and the establishment of a Communist dictatorship. Trotsky and other Marxists established soviets (workers' councils) to continue revolutionary activities, which resulted in a limited but intense second phase of the revolution.

The Marxist movement collapsed within two months, despite their efforts. Trotsky was apprehended, while Lenin escaped to safer regions. Thousands of fatalities, injuries, executions, and arrests were the consequence of the revolution. Trotsky was sentenced to exile in Siberia; however, he managed to evade and eventually joined Lenin in Finland. This is where Trotsky formulated his theory of "Perpetual Revolution," which posited that Communist attacks should continue indefinitely until all regimes were overthrown. This drew him closer to the Bolshevik ideals of Lenin.

At this time, the Bolshevik movement was struggling, having failed to force the Tsar's abdication and disillusioned by the Tsar's hollow concessions in the October Manifesto. Lenin initiated meetings to invigorate the movement, during which he recruited Joseph Stalin, a ruthless and determined revolutionary from the peasant class, acknowledging him as a valuable asset to the Bolshevik cause.

Joseph Stalin, originally named Djugashvili, was born on December 21, 1879, in the small town of Gori near the Turkish border. When Stalin was eleven years old, his father, a shoemaker with a drinking problem, passed away. His mother, determined to provide him with an education, worked tirelessly to support him, hoping he would become a priest. She enrolled him in the theological seminary at Tiflis.

Stalin discovered a network of secret societies at the seminary that advocated for atheistic and revolutionary ideologies, such as the works of Feuerbach, Bauer, Marx, and Engels. Stalin was attracted to these radical ideologies and subsequently became actively involved in clandestine student organizations, abandoning religion in favour of revolution. After nearly three years, his activities were disclosed, and he was expelled from the seminary in May 1899 due to his "lack of religious vocation."

Stalin devoted himself entirely to Marxist revolutionary activity outside of the seminary. Eventually, he became a critical labour agitator for the Social-Democratic party in Batumi, organizing strikes and leading illegal May Day celebrations. His revolutionary activities resulted in his arrest, and he was subsequently sentenced to three years of exile in Siberia.

While in Siberia, Stalin learned about the split between the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks and instinctively aligned himself with the Bolsheviks. The following year, he fled Siberia and returned to Tiflis, where he assumed the role of the chief of the Transcaucasian Bolsheviks. He led a failed uprising in Georgia during the 1905 Revolution and subsequently travelled to Finland to attend a Bolshevik conference and establish contact with Lenin.

Stalin was a devoted aide to Lenin, whom he greatly admired, from that moment on. His zeal for the Communist cause soon became evident, marking the beginning of his influential role in the Bolshevik movement.

Joseph Stalin surreptitiously met with Lenin in Berlin during the summer of 1907 and subsequently returned to Tiflis to coordinate a major criminal operation. This was not a straightforward robbery; rather, it was a violent holdup that demonstrated an abhorrent disregard for human life. A bomb was thrown at a convoy carrying money from the post office to the State Bank, killing horses, several bystanders, and wounding over fifty people, including children. Stalin's associates seized moneybags containing 341,000 rubles during the chaos.

Authorities both within and outside of Russia launched an exhaustive investigation due to the crime's brutality. Maxim Litvinov, Stalin's close associate, was ultimately identified as the source of the stolen money. Litvinov was apprehended in Paris while attempting to convert rubles into francs in order to transfer the funds to Lenin. Stalin was able to avoid capture for several additional years and continued his revolutionary activities, despite the fact that the crime was eventually exposed.

From 1907 to 1913, Stalin worked tirelessly as a union organizer, writer, and Bolshevik leader. In the industrial district of Baku, he gained substantial experience in the art of propaganda, pressure politics, and labour agitation. He ultimately established an effective industrial soviet under his control by organizing tens of thousands of oil workers through a system of legal, semi-legal, and illegal organizations.

Though Stalin was not an effective speaker due to his strong Georgian accent, he became a proficient revolutionary writer during this period. He was the editor of the Socialist newspaper "Dio" in Tiflis, which was renowned for its vehement criticism of the Mensheviks. Subsequently, he contributed to the "Social Democrat", "Zvezda" (Star), and "Pravda" (Truth) in St. Petersburg. It was during this time that he adopted the pen name "Stalin," meaning "Man of Steel."

Lenin established an independent Bolshevik Party in 1912, entirely breaking away from the Social Democrats and appointing Stalin to the Central Committee. Nevertheless, the rise of Stalin was hampered in 1913 when he was arrested and incarcerated in one of the most isolated regions of Siberia. This arrest was just one of many throughout his career; he had been arrested eight times, exiled seven times, and escaped six. Stalin did not attempt to flee during World War I, unlike previous exiles. Rather, he opted to relax and take advantage of his "vacation" in Siberia, thereby avoiding the possibility of being drafted into military service.

By 1914, Europe was teetering on the brink of war, with tensions high among the major powers. The assassination of the heir to the Austria-Hungarian throne by a Serbian nationalist on June 28, 1914, ignited the conflict. Tsar Nicholas II declared war on Austria-Hungary as Serbia was also a target of Russian ambitions, as Austria-Hungary launched its military campaign in search of an excuse to invade Serbia. Germany, allied with Austria-Hungary, declared war on Russia, which in turn led to declarations of war involving France, England, and other nations, plunging Europe into World War I.

The Russian people were unprepared for the psychological and physical toll of the conflict, despite the fact that Tsar Nicholas II had been preparing for war for a long time by constructing a formidable military engine. The Tsar's failure to fulfill the promises of a constitutional government made in the October Manifesto of 1905 had resulted in an increasing tension between him and his people. Although the outbreak of war initially united the Russian people in defense of their country, this unity quickly began to fray.

By 1915, dissatisfaction was widespread, and by 1916, the Russian war effort was faltering. Despite mobilizing over 13 million soldiers, Russia suffered devastating losses: about 2 million killed, 4 million wounded, and 2.5 million taken prisoner. The Ottoman Empire's involvement in the war significantly limited Russia's foreign trade and access to provisions from its allies, and Russian forces were forced to evacuate critical territories. Replacement troops were often so poorly equipped that they had to scavenge rifles from fallen soldiers, and ammunition was so scarce that infantrymen were limited to four shells per day.

The British Ambassador cautioned the Tsar that the Eastern Front could collapse as the situation deteriorated. The Russian populace, which was grappling with food shortages and economic hardship, became increasingly agitated and desertions increased. The cost of living in cities had tripled, while wages barely rose, fuelling discontent among workers and peasants.

Despite these dire warnings, Tsar Nicholas II remained oblivious to the growing crisis, confident he could weather this storm, and to demonstrate his confidence, he announced plans to visit the front lines to boost troop morale. However, the situation had already deteriorated beyond repair, with conditions eerily similar to those that had led to the 1905 revolution. Unbeknownst to the Tsar, his reign was nearing its end, and within months, he would lose both his throne and his life. The stage was set for the Russian Revolution of 1917.

The Dark History of Lysenko

It is said that 200 million people died under communism in the 20th century. Among the many culprits responsible for creating such terrible conditions was Trofim Lysenko, who's 'revolutionary' agricultural concepts cost the Soviet Union and China millions of lives.

Share this post