It is said that 200 million people died under communism in the 20th century. Among the many culprits responsible for creating such terrible conditions was Trofim Lysenko, who's 'revolutionary' agricultural concepts cost the Soviet Union and China millions of lives.

In the turbulent 20th century, the ideology of collectivism, in the hands of totalitarian governance, left a devastating mark, claiming the lives of hundreds of millions. Today, these dark chapters are often relegated to the past. Yet, lurking beneath the surface, the essence of these tyrannical regimes, driven by an insatiable hunger for control and suppression of dissent, echoes through our contemporary society. Even a cursory glance at these notes from the past, much wisdom can be gleaned, for it is a truism to say that there is nothing new under the sun.

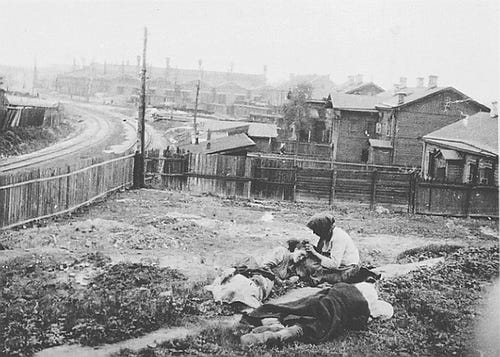

Amid the ruins of Bolshevik leadership after the October Revolution, Russia descended into a series of catastrophic famines. Paradoxically, despite the role of state intervention in exacerbating these crises, the prevailing belief was that further intervention held the key to salvation. This intervention began with a critical re-evaluation of established ideas and the introduction of new concepts tailored to create the 'Socialist Man.' Leading the charge in this collectivist agricultural 'revolution' was the Ukrainian biologist and fervent Leninist, Trofim Lysenko. Driven by a fervent obsession with alternative farming methods, Lysenko was tasked with evaluating crop yields in the Soviet Union.

Lysenko vehemently rejected the conventional theories of Gregor Mendel, dismissing them as 'reactionary science.' (Mendel would later gain posthumous recognition as the founder of modern genetics.) While farmers throughout history had harnessed the power of crossbreeding to enhance desirable traits in plants and animals, Mendel's ground-breaking pea plant experiments, conducted between 1856 and 1863, had laid the foundation for the laws of heredity, known today as Mendelian inheritance.

Rather than the science of Mendel, the Soviet Union embraced the ideas of Jean Lamarck -ideas which challenged conventional thinking. Lamarckism included a rejection of prevailing theories on hereditary traits and an unwavering belief in the largely unproven notion that the use or disuse of part of an organism could influence the genetics of offspring. The acceptance of Lamarckism in the Soviet Union can be traced back to the views of Marx and Engels, who had assumed a synergy between Darwinian evolution and Lamarck's theories (an assumption even Darwin once held).

The rejection of Mendel's ideas, among others, eventually triggered a state-led crusade against 'reactionary' scientific pursuits, giving rise to what is now known as Lysenkoism. With staunch support from the highest echelons of government, virtually all aspects of biological research, from cell biology to basic genetics, were either suppressed or outright banned. Much of this was rooted in the belief that the 'Socialist Man' could reshape nature at his will, a notion vigorously propagated in the realm of propaganda. As historians have duly noted, this campaign inflicted a profound setback on Soviet biology, setting it back by half a century.

After enduring a series of devastating famines and grappling with chronic food shortages, largely exacerbated by the repression and mass deportation of the Kulaks, and to a lesser extent, the Cossack population during the 1920s, the Soviet Union turned to the ideas of Trofim Lysenko as a beacon of hope. Originally championed by the Marxist biologist Isaak Prezent, Lysenko was heralded as a visionary, poised to eliminate the 'bourgeois pseudoscience' that had led to previous agricultural failures.

Following an initial period of success, Lysenko swiftly escalated his attacks on biologists, branding them as saboteurs and 'fascist scientists,' while simultaneously dismissing the value of mathematics in the realm of biology, considering it utterly useless. In a well-documented incident, he equated his critics with peasants who resisted collectivization, all the while under the watchful eye of Joseph Stalin himself, who rose first to applaud Lysenko, providing unwavering support for much of his work thereafter. During this era, manipulated or entirely fabricated laboratory results were disseminated by the state as irrefutable evidence of Lysenko's theories, while his detractors were vilified for pointing out the flaws in his thinking.

In reality, Lysenko's ideas led to smaller crop yields, exacerbating the already dire food shortage. While it is challenging to quantify the precise impact on the Soviet Union, it's clear that his theories hindered potential crop production to the extent that millions of lives were lost to starvation.

Simultaneously, during this tumultuous period, Joseph Stalin's ruthless purges aimed at eliminating his political adversaries, including supporters of Trotsky and many early Bolshevik revolutionaries, were in full swing. Lysenko's ideas soon found refuge under the protective umbrella of Stalin's regime. The chilling consequence of this alliance was the expulsion and execution of numerous critics of Lysenko, particularly those among his contemporaries who had boldly exposed the catastrophic consequences of his 'scientific' theories or possessed the potential to debunk them. Shockingly, more than 3000 of Lysenko's contemporaries found themselves in the crosshairs, facing arrests, executions, terminations, blacklisting, or utter professional discreditation.

Lysenko’s ideas were not isolated to the Soviet Union. The Chinese government, also motivated by a disdain for 'reactionary' Western science, chose to integrate Soviet ideas into its policies. This was especially so during the launch of the “Great Leap Forward”, an ambitious initiative aimed at propelling China into a new era of prosperity. Although Lysenko's ideas had been adopted immediately following Mao's victory in the aftermath of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, their large-scale implementation did not commence until the late 1950s, coinciding with the onset of the Great Leap Forward, in an attempt to boost agricultural productivity.

A pervasive tactic employed in Chinese agriculture at the time was Lysenko's ideologically driven notion that plants of the same 'class' would not compete. This led to the recommendation of planting seeds close to each other, with the belief that they would not compete due to their shared 'indifference.' Furthermore, it was advised to triple-seed the crops. However, much like in the Soviet Union, this approach failed spectacularly, resulting in diminished crop yields.

Another misguided idea was that of “deep ploughing”, championed by Soviet agriculturalist Terentiy Maltsev, who claimed it was universally applicable to all crops, though in reality, it benefited only specific plants. Lysenko promoted Maltsev's beliefs, and they were adopted by Chinese collective farms. This involved indiscriminately planting all seeds much deeper into the ground, based on the premise that deeper soil would be more fertile, leading to stronger roots and increased growth.

Both of these approaches were complete failures during the initial year of the Great Leap Forward, which culminated in the Great Chinese Famine. A famine which persisted for several years and claimed the lives of tens of millions of people. Some estimates suggest as many as 60 million perished during this period.

As startling as these figures are, Mao Zedong was initially unaware of the extent of the catastrophe. He was presented with falsified evidence suggesting that Lysenko's methods had resulted in crop yields skyrocketing by 1000% to 3000%. The deception achieved by forcibly uprooting existing crops and replanting them in specific fields before Mao's arrival, creating the illusion of astounding success. Officials overseeing these collectives exploited and overworked the peasants to maintain this facade until Mao was finally informed of the massive failure nearly a year later.

In response to this revelation, Mao sought to demonstrate 'solidarity' with the suffering farmers by reducing his own food consumption throughout 1960. Years later, he would use this famine as political leverage to reclaim the Communist Party's leadership and appeal to the workers, particularly their children, who had endured immense hardship. This marked the beginning of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, during which Mao blamed capitalism for many of the nation's woes. Mao's reluctance to admit to agricultural failures only deepened the severity of the famine.

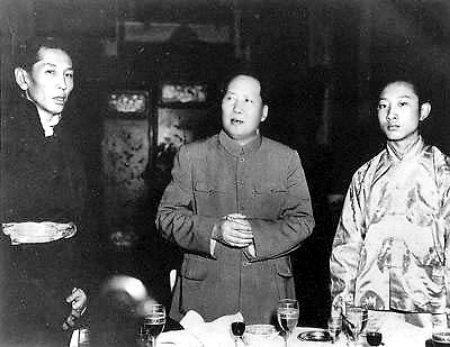

One infamous example of the state's deliberate suppression of information about the famine was the 70 thousand Character Petition authored in 1962 by Tibet's 24-year-old Panchen Lama. In addition to exposing the general brutality of the Chinese Communist Party against the Tibetan people, the petition detailed the various forms of repression stemming from the Great Leap Forward. This included forced abortions, religious suppression, the imposition of 'class warfare' on Tibetan society, and a comprehensive account of the famines directly resulting from China's policies. The Panchen Lama described the famine as unimaginably horrific, even 'in your worst dreams.' Regrettably, the letter remained hidden from the public, and the Panchen Lama himself would be subjected to 'struggle sessions.' This letter was written in response to a personal meeting with Mao, in which he informed Mao of the famines in Tibet, yet saw no policy changes following the meeting.

Mao Zedong led his country on a perilous journey of untested ideas. Such ill-fated experiments played a crucial role in the tragic toll of lives during the Great Leap Forward, an era marked by state-sanctioned incompetence, an aversion to acknowledging failures, and a stark disregard for the welfare of the Chinese people.

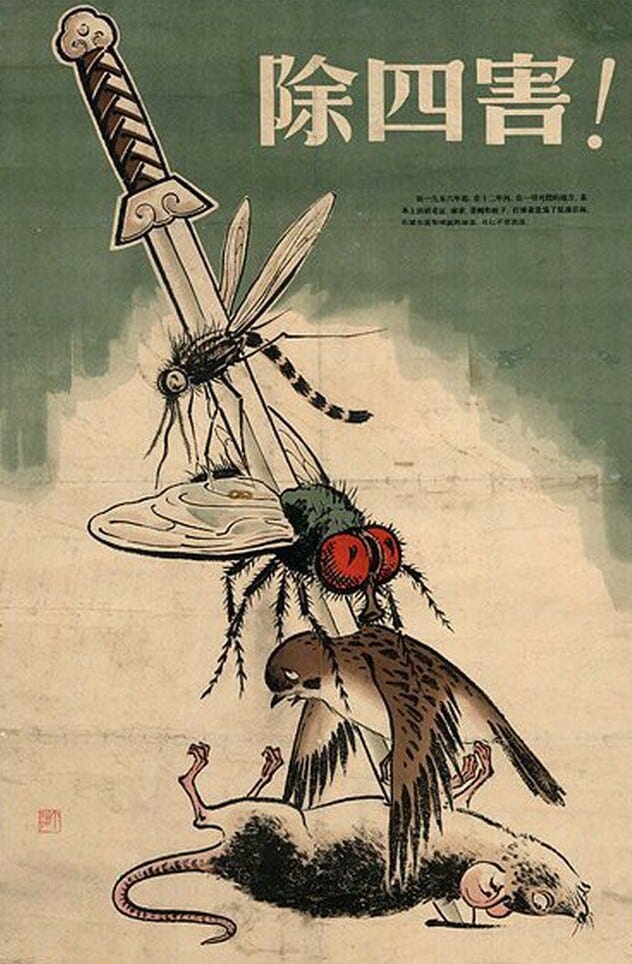

One of the most notorious examples of this state-driven madness was the nationwide campaign to combat animal-borne diseases, which the government claimed were chiefly caused by four species: mosquitoes, rats, flies, and sparrows. This initiative became infamously known as the Four Pests Campaign.

State authorities alleged that sparrows posed a grave threat, with each bird purportedly devouring four kilograms of grain annually. Citizens were tasked with exterminating sparrows by any means necessary, and tragically, that's precisely what happened. Peasants resorted to poison, firearms, and even stood near trees, noisily clanging metal objects until the exhausted birds fell from the sky. By the following harvest season in 1959, sparrows had been nearly eradicated. However, it soon became evident that sparrows were not the primary grain-eating pests; locusts were. With their natural predator, the sparrow, obliterated, locust populations exploded, unleashing crop devastating swarms. The Great Chinese Famine, already exacerbated by Lysenkoism, just got worse.

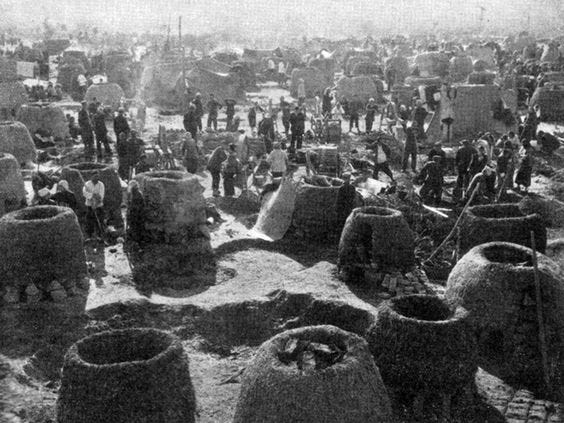

But the litany of errors didn't end there. During the Great Leap Forward, Mao fervently sought to elevate China to the pinnacle of global steel production, envisioning the nation as the world's largest producer. Small blast furnaces were haphazardly constructed across the country, often in peasant communes. Despite their utter lack of metallurgical knowledge, Mao not only championed the endeavour but vehemently defended it when problems began to surface. Initially, peasants grappled with a shortage of fuel, prompting them to throw anything flammable into the furnaces, including wood from coffins and depleted forests (rapid deforestation was another pressing issue at the time). As if this weren't enough, there was a scarcity of adequate materials for steel production. Peasants, utterly ignorant of metallurgy, began melting down random objects, including old coins and kitchen utensils, and eventually resorted to smelting their own tools. After transmuting practically anything remotely resembling metal into molten slag, the final predicament emerged: most of the blast furnaces were producing pig iron.

Part of the problem stemmed from Mao's disdain for intellectualism; he dismissed expert consultations on how to resolve these issues. It took over a year before Mao visited an actual steel plant, where he was finally enlightened about the necessity of large coal-fired plants for steel production. Nevertheless, he persisted with the campaign, fearing that any halt would dampen the revolutionary spirit.

These notes from the past send an unequivocal message: ideologically driven centralized governing bodies, dictating every facet of a society's choices, are bound to fail. Such systems are inherently incapable of comprehending, let alone directing, the complexities of an economy or society. Rather, navigating these intricacies, through individuals and autonomous entities with the requisite expertise, is the better way. When centralized planning falls into the hands of a select few ideologically driven individuals (who forsake basic logic in favor of perpetuating their own hold on power), there is only misery for the masses.

During the 20th century, collectivism managed to kill hundreds of millions of people. Today we consider these things, if we consider them at all, a past issue. However, at the core of these tyrannical societies was a drive for complete control and suppression of dissents which has made itself evident in today’s society yet again. There is much to be learned…

Following the catastrophic failures of Bolshevik leadership following the October Revolution, Russia was plunged into several disastrous famines. Despite often being a result of state intervention, it was decided that the only way out of this continual misery was further intervention. This would begin with a (critical) look at accepted ideas, and the introduction of new concepts suited for ‘Socialist Man’. At the forefront of this collectivist farming ‘revolution’ was Ukrainian biologist and devout Leninist Trofim Lysenko. Obsessed with alternative methods of farming, Lysenko was given the task of bettering productivity in the Soviet Union by increasing crop yields.

Lysenko rejected the commonly held ideas of Gregor Mendel as ‘reactionary science’. (Mendel gained posthumous recognition as the founder of the modern science of genetics.) Though farmers had known for millennia that crossbreeding of animals and plants could favour certain desirable traits, Mendel's pea plant experiments conducted between 1856 and 1863 established many of the rules of heredity, now referred to as the laws of Mendelian inheritance.

Instead, the ideas of Jean Lamarck were taken as truth. This included a rejection of most theories relating to hereditary traits, and a blind acceptance of the largely unproven claim that bodily changes influence genetics and offspring. Lamarckism was widely accepted in the Soviet Union prior to the rise of Lysenko. This primarily came as a result of the views held by Marx and Engels, some of which were built around an assumption that Darwinian evolution and Lamarck’s theory were both true and both mutual (Darwin originally believed this as well).

This rejection of Mendel’s ideas (among others) eventually resulted in a state campaign against reactionary areas of research. This movement became known as Lysenkoism. With support from the highest levels of government, everything from cell biology to basic genetics research was repressed or outright banned. Much of this was oriented around the belief that Socialist (Soviet) Man could reorganise nature according to his will (this idea was explicitly pushed in propaganda). As historians have noted, this campaign would set Soviet biology back half a century.

IDEAS IN ACTION

Following several famines, and a continued shortage of food, thanks primarily to the repression and mass deportation of the Kulaks (and to some extent the Cossack population) during the 1920s, the Soviet Union began pushing Lysenko’s ideas as truth. Originally promoted by Marxist biologist Isaak Prezent, Lysenko was hailed as a genius who would weed out the ‘bourgeois pseudoscience’ which had resulted in past failures.

After some initial success, Lysenko quickly took to denouncing biologists (who were labelled as saboteurs and ‘fascist scientist’) and rejecting the utility of mathematics in biology (he thought mathematics useless). In one well known incident, he compared those who criticised his ideas to the peasants who resisted collectivisation, while Stalin himself sat in the audience. Stalin was the first to stand and applaud Lysenko, and would back much of Lysenko’s work from that point on. During this time, manipulated or completely falsified lab results were publicised by the state as proof of his theories. Yet again, his critics were demonised for highlighting the flaws in his thinking.

In actuality Lysenko’s ideas were resulting in smaller crop yields than before, exacerbating the lack of food. Although it is hard to determine how much of a direct impact this had on the Soviet Union, his ideas prevented potential crop yields to the point that millions starved.

REMOVING COMPETITION

During this same time, Stalin’s purges against his political rivals - including supporters of Trotsky and many Bolshevik revolutionaries - was in full swing. The ideas of Lysenko soon came under this banner of protection. The result was the removal and execution of many of Lysenko’s critics, particularly targeted at those of his contemporaries who had highlighted the dramatic outcomes of his ‘science’, or had the potential ability to disprove his theories. Over 3,000 of his contemporaries were targeted, being either arrested, executed, fired, blacklisted, or otherwise discredited.

This should come as little surprise, since much of Lenin and Stalin’s reign was solidified by the assurance that critics would be met with bullets. Thus, Lysenkoism continued despite the obvious evidence of its large scale failure.

THE GREAT LEAP FORWARDS

Despite this controversy and the setbacks caused by the rejection of Mendel’s ideas, the Chinese government had agreed that Soviet ideas would be integrated in future decisions, largely motivated by a similar dislike of ‘reactionary’ western science. This included spearheading the Great Leap Forward, with the goal of leading China into a new era of prosperity.

It was in China where Lysenko’s ideas had the most profound impact. Although they had been adopted immediately following Mao’s victory (following the Chinese Civil War in 1949), the large scale implementation would not begin until the late 1950s, as the Great Leap Forward was set in motion, with one goal being increased agricultural productivity.

The most pervasive tactic applied to farming was Lysenko’s (ideologically motivated) idea that plants of the same ‘class’ would not compete against one another. He recommended seeds be planted in close proximity to one another to increase yields (since no plants would compete due to indifference…) and then triple seed them following this. Just as in the Soviet Union, the idea once again failed, resulting in small crop yields. Another idea was deep plowing, which Soviet agriculturalist Terentiy Maltsev claimed was applicable to any crop (in actuality, only specific plants benefit form this). Lysenko pushed Maltsev’s beliefs, which were then adopted by Chinese collective farms. Farmers began plowing and planting seeds far deeper into the ground, on the premise that deeper soil was more fertile, and would result in stronger roots and increase growth.

Neither of these ideas resulted in any benefit, instead exacerbating existing problems. In fact, the failures during the initial year of the Great Leap Forward resulted in the Great Chinese Famine, which lasted for several years and killed tens of millions of people (some estimates put the figure as high as 60 million).

As one would expect from such a government, the results of these colossal failures were both censored and falsified. In fact, Mao himself (who was aware of some issues, but initially kept in the dark about this) was presented with falsified evidence that Lysenko’s methods resulted in crops with 1,000% to 3,000% increases in yields. This was done by forcing farming communes to carefully pull existing crops and replant them in specific fields before the arrival of Mao, giving the illusion of incredible success. Officials in charge of these collectives abused and overworked the peasants to keep up this charade until Mao was finally informed of the massive failure nearly a year later.

Mao stood in ‘solidarity’ with the farmers after discovering this, by decreasing the amount he ate throughout 1960. He would use this as fuel several years later to retake the Communist Party and appeal to the workers (and particularly their children) who had suffered, culminating in the Chinese Cultural Revolution (of course, he would blame capitalism). Despite his uncertainty regarding the agricultural problems, many others issues were known to him, and an unwillingness to admit failure only worked to worsen the famine.

A famous example of the state knowingly repressing information regarding the famine was the 70,000 Character Petition written in 1962 by Tibet’s 24 year-old Panchen Lama. Alongside calling out the general brutality of the CCP against the Tibetan people, he detailed the various forms of repression resulting from the Great Leap Forward, including forced abortions, suppression of religion, superimposition of ‘class warfare’ onto Tibetan society, and a detailed report on the famines directly caused by China’s policy. He observed that the famine was the worst ever seen in Tibet, unimaginable “even in your worst dreams”. The letter was hidden from the public, and the Panchen Lama would eventually be subject to struggle sessions. His letter was written in response to a personal meeting with Mao, in which he informed him of the famines in Tibet, but saw no change in policy after the meeting.

REPLICATED INSANITY

In the same manner, Mao Zedong experimented with untested ideas, using the Chinese population as his test subject. These failed ideas helped push so many more to die during the Great Leap Forward. A mixture of state sanctioned incompetence, an unwillingness to admit failures, and a disregard for the Chinese people lead to the deaths of tens of millions.

The most famous example of this state enforced insanity was a nation-wide push to reduce animal-spread diseases. According to the state, four primary species were responsible for hardening the life of the Chinese man; mosquitos, rats, flies, and sparrows. This would become known as the Four Pests Campaign.

State officials claimed that sparrows were particularly damaging, with each bird supposedly eating four kilograms of grain per year. Citizens were to kill off these sparrows by any means, and that is exactly what happened. Peasants used poison, guns, and would even stand near trees clanging metal objects until the birds dropped from the sky in exhaustion. When harvest time came the following year (1959) the sparrows had been eradicated, pushing them to near extinction. As it turned out, the sparrows were not the primary pest eating grain, but locusts. With their natural predators wiped out, swarms of locusts swept across China, with the insects population reaching unnaturally inflated sizes. Crops were wiped out. This worsened the Great Chinese Famine which was already in full swing thanks to Lysenkoism. This mirrors the Soviet Unions ‘tree tax’ campaign, in which farmers were forced to pay tax on each tree on their land, resulting in poor farmers cutting them down, leading to food shortages.

But wait! There’s more... During the Great Leap Forward, an attempt was made to increase China’s steel production, with Mao hoping the nation would become the biggest producer in the world. Small blast furnaces were manufactured and assembled across the country, often in peasant communes. Despite having no understanding of metalwork, Mao both pushed the project and staunchly defended it when failures began to arise. Among the first problems faced by peasants was a lack of fuel. In response, anything flammable was thrown into the furnace, including wood from coffins and deforested trees (rapid deforestation was also causing major issues at the time). Then there was a lack of sufficient material to produce steel. Peasants (with no knowledge on metallurgy) began using random objects (including old coins and cooking utensils), before finally smelting their own tools. After turning practically anything resembling metal into molten gel, the final problem presented itself; most of the blast furnaces were producing pig iron.

This partially resulted from Mao’s hatred of intellectualism. He had rejected consultations on how to overcome this issue. After more than a year of this, Mao finally visited an actual steel plant, where he was informed that large coal-fire plants are required for steel production. Despite this, he continued to push his campaign, claiming that a halt would dampen the revolutionary spirit.

There are other examples, but the point is clear. Centralised governing bodies dictating the choices of everyone does not work. It cannot account for the complexity of an economy or society. Only individuals and autonomous companies with the required expert knowledge can do that. Things are made even worse if the centralised planning is being done by a small set of ideologically driven individuals who reject basic logic in favour of re-validating their own claims to power.

FINAL WORDS

Maoist China and the Soviet Union demonstrated, with shocking devastation, what dictatorships can do to a population when ideology is followed blindly. With little to no reference to empirical evidence, or just common sense, a centralised power wielding an iron fist for ideological purity proves time and again to be deadly.

Notes From The Past is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The man who exposed the Soviet Union

After being unjustly sent to the gulag, Alexander Solzhenitsyn would being writing about his experiences. His writings - which exposed Stalin, Lenin, and the rest of the communist system - would have far reaching impacts on Russia and the world.

Share this post