After being unjustly sent to the gulag, Alexander Solzhenitsyn would being writing about his experiences. His writings - which exposed Stalin, Lenin, and the rest of the communist system - would have far reaching impacts on Russia and the world.

Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, there was a strong temptation toward communism in the West. And this persisted through the first half of the 20th Century, even as evidence grew of the huge failures within the Soviet Union and China. Despite the damning evidence from communist states, the sway of this ideology only increased in the west, culminating in the American counterculture of the 1960s. Throughout this period Alexander Solzhenitsyn had been painstakingly documenting his own, and other’s, experience of communism: stories of unjust imprisonment, forced labor to near death, and some of the worst atrocities of the 20th Century. His writing would become some of the most damning revelations of the Soviet Union, and would alter the course of the Cold War.

WHO WAS HE?

Alexander Solzhenitsyn was born in 1918 in western Russia. Shortly before his birth, his father - a Russian soldier - was killed in a hunting accident, leaving him to be raised alone by his mother - a Ukrainian who’s family property had been seized and turned into a collective farm. In an act of defiance, his mother chose to raise him an Orthodox Christian, an upbringing frowned upon by the atheistic socialist state.

By the mid 1930s, Alexander had travelled to Rostov State University, where he studied mathematics and physics. During this time, he had also taken courses from the Moscow Institute of Philosophy, Literature and History. He recalled later that he went through this period of his life without really questioning the ideology of the state.

During World War 2, he served in the Red Army, working with artillery. Travelling west, he occasionally wrote letters, in which he questioned the prevailing narratives put forward by Stalin and his government. Little did he realise, these letters had been intercepted by the Red Army’s counter intelligence. In February 1945, he was arrested in East Prussia. Charged under the broad “Article 58”, he was accused of anti-soviet propaganda, and founding a hostile organisation under Article 11, to which he was charged with eight years of forced labour.

IMPRISONMENT

He was sent to prison, where he would circulate through the brutal ‘gulag’ system. In the gulags he met countless individuals who shared their stories of unjust arrests, while others spoke of the terrors and crimes committed by the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (known as the NKVD). With millions flowing through the gulag system, there was no shortage of finely detailed stories of the brutal regime. Solzhenitsyn began to compile testimonies, research, and his own experiences, and would use this material to craft several literary works. Using various methods to catalogue and remember details, he managed to hold out in the harsh gulag conditions until 1956 while remembering volumes of stories.

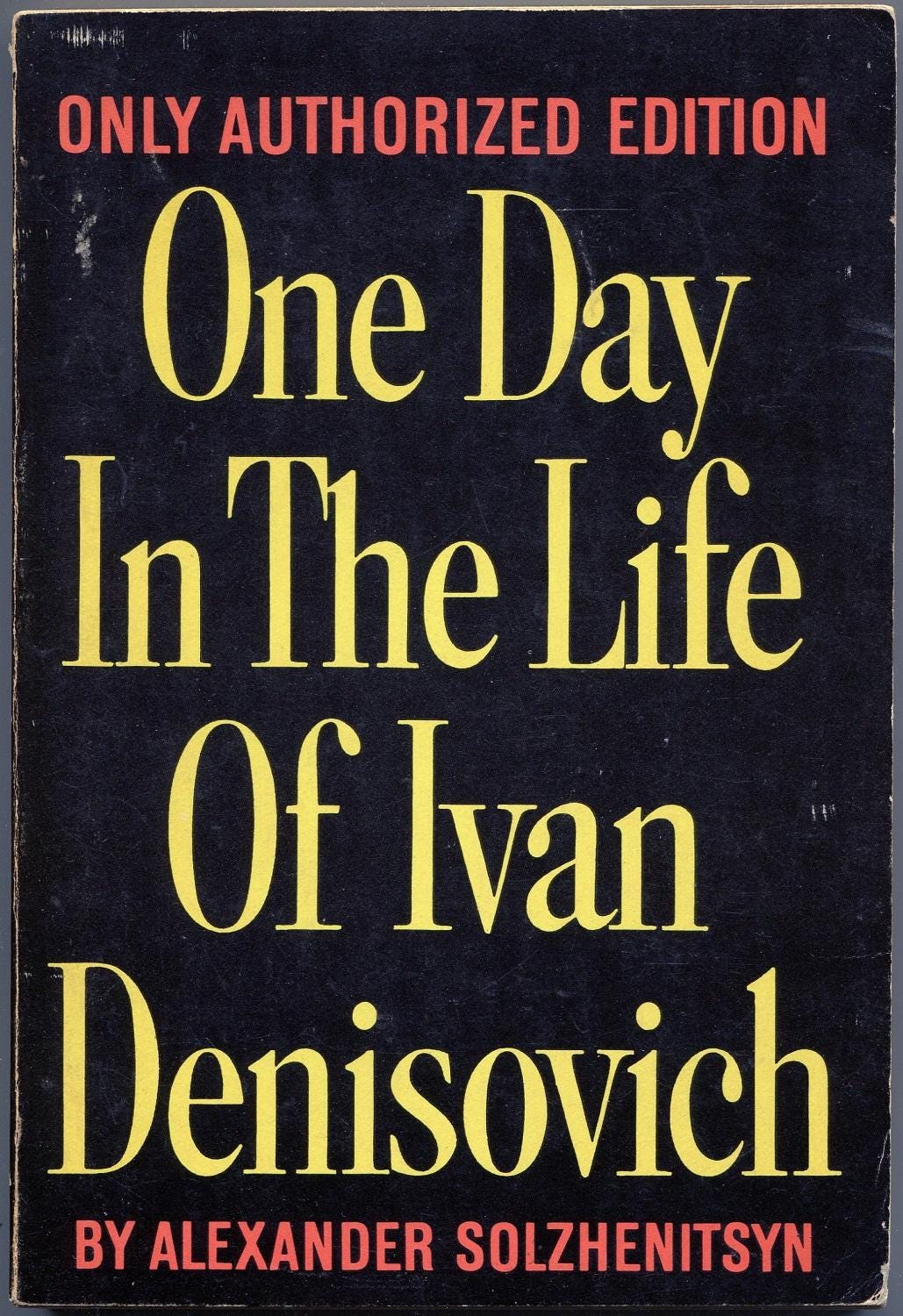

In 1956, during what would become the beginning of the ‘thaw’ under newly established leader Khrushchev, Solzhenitsyn was released. Shortly after, he began to secretly write, using the information he gathered in the gulags. The first of these works was a short novel - One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich - and was completed in 1960. In what could have potentially had him arrested, Solzhenitsyn submitted the work to Aleksander Tvardovsky, a magazine editor, with the hope of it being printed. In an amazing turn of events, the manuscript found its way to Khrushchev himself, who, having read it, gave explicit approval to publish it. Khrushchev defended the work, which would have been impossible just a few years earlier, claiming that it was about time the Soviet Union admitted the catastrophic failure of Stalin.

Ivan Denisovich was a work of fiction about a gulag prisoner who had been wrongly imprisoned. The novel was written to highlight the inhumane nature of the gulag system, and the repressive nature of Stalin’s regime as a whole. These events were not distant memories. The book was set in the early 1950s, and was a critique of fairly recent events. Thus, the publication of this work was all the more groundbreaking, as no criticism of the Stalinist regime had been legally circulated within Russia before this time.

GULAG ARCHIPELIGO

However, this good favour didn’t last long. Despite the outward appearance of support, Solzhenitsyn was under close surveillance by the Soviet secret police. While there had been a grace for him to publish such a literary work as Ivan Denisovich, there would be little scope for him to expose the state any further. His next work would be exhaustive in detail, exposing everything that had been happening in the Soviet Union up until that point. It would go beyond Stalin, and implicate Lenin, Trotsky, and others. It would highlight critical events such as the October Revolution, the early Lenin days, and the flaws in the very ideology that lay at the foundation of the state. The secret police, from their monitoring of Solzhenitsyn, had suspicions that such a book was in the works. Thus, to preserve the project, Solzhenitsyn created elaborate methods of writing, in which he would travel to various friends houses, create duplicates of the book, and distribute them in portions to various others he knew he could trust.

Such a book must have been perceived as a great threat to the state, as an attempt was made on Solzhenitsyn’s life in 1971. Supposedly, the KGB had used the toxic chemical Ricin - infused into a gel - to secretly assassinate Solzhenitsyn. He did fall seriously ill, but ultimately recovered from the attempt on his life.

The Gulag Archipelago would become his most successful and most important work. The book’s details, testimonies, recollections, and explanations laid bare the true nature of communism, and exposed the decades of brutality that had occurred under the Soviet system. Ever since the October Revolution in 1917, the western world had heard rumours and some testimonies of Soviet atrocities. However, through various methods, the Soviet government, and intellectuals in the west, had successfully downplayed or suppressed the reality of what was really going on.

For example, many western media publications supported the Soviet experiment during the 1920s. By the 1930s, the Soviets had paid-off western journalists to write outright lies, most famously, Walter Duranty of the New York Times, who was paid by Stalin to ignore the Ukrainian Famine of 1932, receiving a Pulitzer Prize for his so-called ‘journalism’. A prize, which has, to this day, never been revoked. This pro-soviet rhetoric within the western press would only expand during World War 2. With the Soviets as allies, western nations - particularly England, which had an incredibly strong pro-communist government - willingly went along with the lies of Stalin, even going as far as to repatriate fleeing refugees from Russia - with no actual justification - in what was known as Operation Keelhaul. Many of these Russians were English citizens, who had lived in England from before the Russian revolution. There were also anti-communist Yugoslavians and Hungarians who were also arrested, often without good reason, and handed over to Soviets and pro-Soviet Partisans in Yugoslavia, where they were brutally executed. In all, 2.5 million people were forcibly repatriated throughout Europe, with many being illegally arrested and deported from England and even from New Jersey in America.

The publication of Solzhenitsyn’s account of socialism in action had far reaching consequences, especially in the milieu of the Cold War. One of the most important being the impact it had on socialist intellectuals. Up until this point, despite rumours and even evidence of many horrors occurring within socialist states, there was still intellectual support for the likes of Mao Zedong, Lenin, and Stalin. American and French university campuses - for example - were regularly adorned with Maoist and Leninist ideologues, who would promote socialist and communist ideals. However, with the publication of the Gulag Archipelago, these movements were exposed. Consequently, many socialist intellectuals turned to other forms of revolutionary expression, including Herbert Marcuse’s Critical Theory and Antonio Gramsci’s concepts on education, which had not yet been tainted with the same bad reputation.

The book was also key to a revival of scrutiny and suspicion surrounding the Soviet Union in the late 1970s and 1980s, after nearly two decades of pro-socialist sympathy being expressed within the United States. The true impact of Solzhenitsyn’s work in this sense is hard to gauge, although it likely helped to accelerate the western view on the Soviets, and speed up its inevitable collapse.

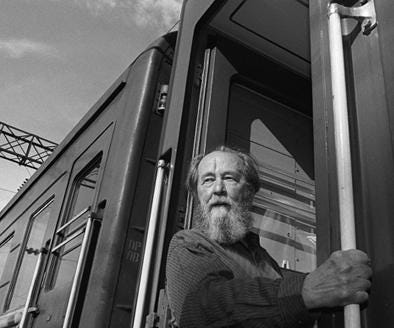

Following the release of the Gulag Archipelago manuscript, Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Soviet Union and stripped of his citizenship in February 1974. From this point on, he would become well known both in the east and west. However, in his home country, he would be slandered. Pravda - the famous Soviet newspaper - would write many hit pieces, attacking his character, including claims that he supported Nazi movements in Ukraine and Russia, and that the Gulag Archipelago was written out of a hatred for his own country. These allegations were of course false. In 1994, after twenty years in exile, he would return with his family to Russia.

CONCLUSION

The writings of Solzhenitsyn were crucial in exposing the true nature of collectivist systems which reject human dignity in favour of top-down-control. Although times seem to have changed, the dangers remain the same. The warnings of Solzhenitsyn are just as pressing today as they have always been. After all, there is nothing new under the sun - these ideologies may change their language and context but fundamentally remain the same. Having exposed a totalitarian system once before, Solzhenitsyn’s writings can once again expose current and future attempts at totalitarian control.

It is said that Mao Zedong admitted that “Communism is not love. Communism is a hammer which we use to crush the enemy.” Let us be careful to see the emblems of the hammer and sickle, or the raised fist, from the lived experience of Solzhenitsyn, lest we be seduced to embrace such ideologies ourselves.

Notes From The Past is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Like History Documentaries? Support our sponsor, History Fix. To get 30% discount on the first year of an annual subscription, use the code 30PERCENTOFF

Share this post