The French government signed an armistice with Germany in mid-1940, which was effective from June 22nd onward, following the fall of France. This would, as the French hoped, put an end to the regional conflict in France and restore a measure of security. England, which had by this time withdrawn from mainland Europe, was not pleased with this decision. Churchill, in particular, was incensed by France's decision. They were now a neutral nation, situated between England and Germany.

Churchill called on parliamentarians to condemn France on numerous occasions for its unwillingness to fight to the death, which he regarded as a betrayal of England. By July 1940, Churchill had made the decision to begin military operations against neutral France - against the same troops they had just weeks earlier been fighting alongside in Europe.

The French Navy was the principal objective for Churchill. At that time, the majority of the French navy was operating in French North Africa or in the vicinity of Toulon, while the remaining ships were located in the French colonies of the Caribbean or in close proximity to Egypt. Churchill and his advisors maintained that the French navy was a threat, despite its neutrality. Churchill believed that the Germans may capture the ships and use them against England, and this was the rhetoric he would use to justify operations against them.

However, the fact was that neither the Germans nor the Italians possessed technology that was suitable for use on French ships. Numerous incompatibilities existed. Furthermore, Germany and Italy believed that any attempt to seize these French ships would result in mutiny or the crews fleeing to England with the ships. Consequently, the notion that the Axis powers were preparing to commandeer these vessels was entirely unfounded.

On June 27, Britain made one more attempt to compel the French to violate their neutrality and use their Navy to fight in the Mediterranean before deciding to engage in military action. However, the British were unsuccessful. Admiral Francois Darlan, the commander of the French Navy, had assured the British that they would not allow their ships to be captured by any other nation and that the French would not launch an attack on the British.

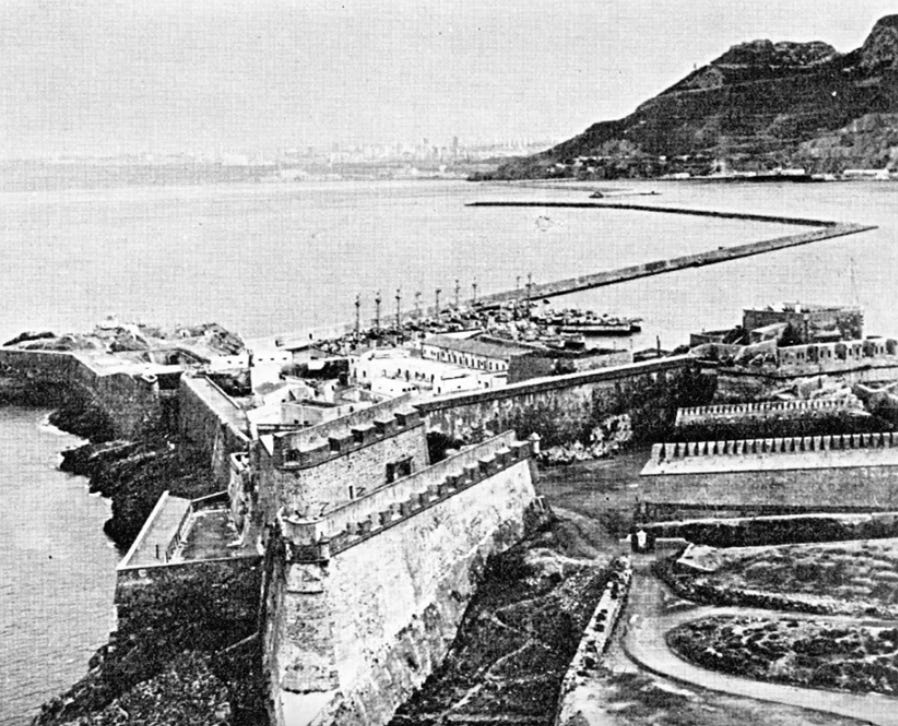

Nevertheless, with military approval Churchill moved towards what would become known as Operation Catapult. The objective was the surprise attack and destruction of the neutral French Navy. Even though Toulon was extensively fortified from the land, North Africa had more minimal defenses around its ports which held some of the most powerful French ships.

The Admiralty of the Royal Navy was opposed to the attack. They believed that if they were to proceed, they must be certain that they could inflict a substantial amount of damage on all the ships. Even then, they were aware that this could result in a war with France, which would turn the French colonies against the British, further limiting their options for operating in the war. Broadly speaking, it was an operation which made no sense, and would only damage Britain's reputation.

The operation was scheduled to commence on July 3, 1940. An ultimatum was to be issued to French Admiral Marcel-Bruno Gensoul, who was in charge of a formidable fleet at Mers-el-Kebir. British Admiral James Sommerville, who was stationed in Gibraltar, was assigned the duty of delivering this ultimatum to the French. He assigned the task to the commander of the carrier HMS Ark Royal, who was fluent in French.

Realising that Sommerville himself was not present, Gensoul replied by sending a less-senior officer. This resulted in confusion and delay in the hours that followed. Nevertheless, the main points in the ultimatum reached Gensoul, which essentially directed the French to violate their neutrality armistice and commence attacks on the Germans, thereby resulting in the return of war in France.

Gensoul said it was untenable to accept such a demand and instructed his officers to prepare for a confrontation with the British. Admiral of the French Navy - Francois Darlan - could not be reached.

British operations in Alexandria, Portsmouth, and Plymouth began that evening. Royal Navy personnel snuck onto French ships and took control, and in some cases fighting broke out, resulting in several casualties. However, the primary assault would occur at Mers-el-Kebir.

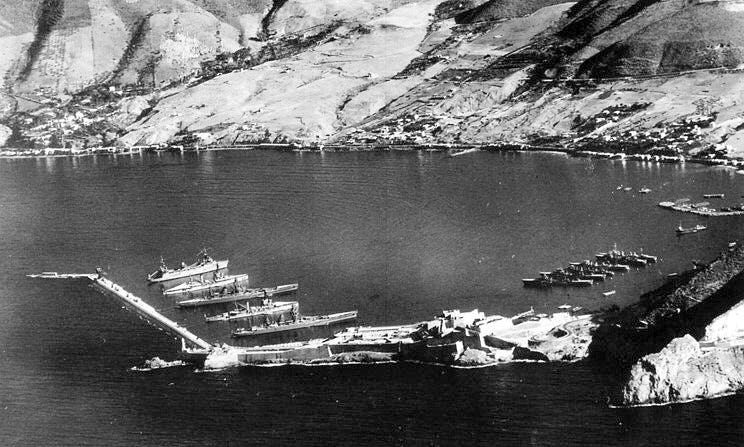

A squadron of British Blackburn Skuas and Fairey Swordfish flew over the port before negotiations had even finished, dropping magnetic mines at the exits. The British force was closing in, consisting of an aircraft carrier, two battleships, a battle cruiser, and an escort of several cruisers and destroyers.

The call went out to French submarines based at Oran, and battleships at Algiers to head to Mers-el-Kebir for the imminent battle.

On the following day, July 4, the British ships were now within range, and the order was given to commence fire at 5:57 p.m. With the British in open waters and the French confined to port, there was limited opportunity to alter the course of the battle.

Within just nine minutes, the French ship Bretagne sunk with 977 of her crew. Substantial damage was sustained by other vessels. Submarines had arrived from Oran by this time; however, they were promptly intercepted by British aviation, and cruisers were able to suppress them.

Sommerville was informed that French naval forces from Algiers would shortly arrive to provide assistance to those who were stranded in port. Planes observed eight cruisers and numerous destroyers. Sommerville was of the opinion that the French reinforcements would surpass his own force in size and that they would be in a superior position when they arrived by night, as the moon would rise behind the British fleet, resulting in a silhouette.

Leaving Mers-el-Kebir, the British believed that perhaps they had not inflicted enough damage upon the ships at port. Consequently, two additional assaults were conducted a few days later. Two torpedo attacks were conducted by Swordfish aircraft, launched from a carrier. These attacks resulted in additional damage to French ships, and the sinking of one.

The assault was not insignificant in terms of magnitude. A total of 1300 French soldiers perished and 350 were wounded. That is approximately half of the number of casualties that the Japanese inflicted upon Americans at Pearl Harbor. However, it is obvious why the fateful events at Mers-el-Kebir never received the widespread recognition as Pearl Harbour did. In an effort to impede the Germans, the British launched a vicious attack on a former ally. No matter the outcome of the war, nothing could atone for the nearly 1700 dead or wounded Frenchmen who perished at the hands of the British.

Historians nowadays have attempted to gloss over the horrible realities of the attack. Certain individuals have asserted that it was merely a symbol that the British would continue to fight heroically, which is evidently a form of appeasement. The French would likely disagree.

Following the assaults, Churchill would declare that it was the most painful decision he had ever been compelled to make. Politically, it was a different story. The assault bolstered Churchill's popularity among conservatives, surpassing that of his predecessor, Neville Chamberlain. Eric Seal, Churchill's private secretary, also stated that the principal motivation behind the attack was to elicit a response from the Americans. The intended positive consequences of the assault are a topic of debate among historians. George Melton, however, argues that it only served to exacerbate the situation and that resources would have been more effectively devoted to attacking the Italians. Rather, Melton contends that Churchill's decision was the consequence of his revulsion toward the French for their surrender and his fixation on the destruction of France's four modern battleships—the Dunkerque, Richelieu, Jean Barp, and Strasbourg.

Admiral Somerville said that it was “the biggest political blunder in modern times and will rouse the whole world against us. We all feel thoroughly ashamed.”

In France, hatred for the British was stoked once again. The assault served as a reminder to them that the British were prepared to destroy a neutral nation's fleet at the whim of a single politician, Winston Churchill, who was primarily motivated by political ambitions and personnel compulsions.

The British Admiralty correctly observed that the attack lacked strategic logic. The French were essentially betrayed by a former ally, alienating them from the British, threatening to impede Allied opportunities in Europe and North Africa. Britain's prospects in the European theater were limited if the United States had not intervened.

The legacy of the Mers-el-Kébir attack is one of deep controversy and lasting impact on Anglo-French relations, and many would agree, a senseless loss of life and materiel.

Donate:

Bitcoin (BTC): bc1qytnwn0ht8p98cxs420h5kjf738unzauqd7f0rq

Share this post