Part 1 of a three part series on communist activity in America during the 20th Century.

Over the past few years, a number of old interviews with a Russian defector have come to prominence. Yuri Bezmenov, who defected from the Soviet Union in 1970, detailed in a set of talks from the 1980s how America had been infiltrated by communists, with the aim of being completely subverted and destroyed. His disturbing warnings, made roughly 40 years ago, predicted the ideological defeat of America within a few decades. As many have noted, he doesn’t seem to have been far off the mark. How did this come about? And is such subversion leading to the imminent destruction of America, and indeed, the West?

EARLY HISTORY

Let us go back a century to consider the rise of several prominent intellectuals, who may offer keys to the subversion of American culture. As Bezmenov has described, many subversive tactics had come out of the Soviet Union, but as time went on, such things would spread, like a virus, no longer relying on the Soviets, but operating independently, within a new host nation.

19th and early 20th century revolutionary theorists (most prominently the Marxists) believed that violent revolution could be achieved through the rallying of the working class and the peasants. These people, as Marx wrote, could unite and throw off the chains of capitalism. Marx claimed that capitalist systems would inevitably collapse under their own weight, and that socialism would be inevitable. Most theorists predicted that what was necessary to start this chain reaction was revolution. In 1917, a communist revolution did occur in Russia. However, it did not ignite a global workers revolt. Whats more, it happened in a feudal country, not a capitalist state. The Marxist theory had missed the mark on some basic assumptions.

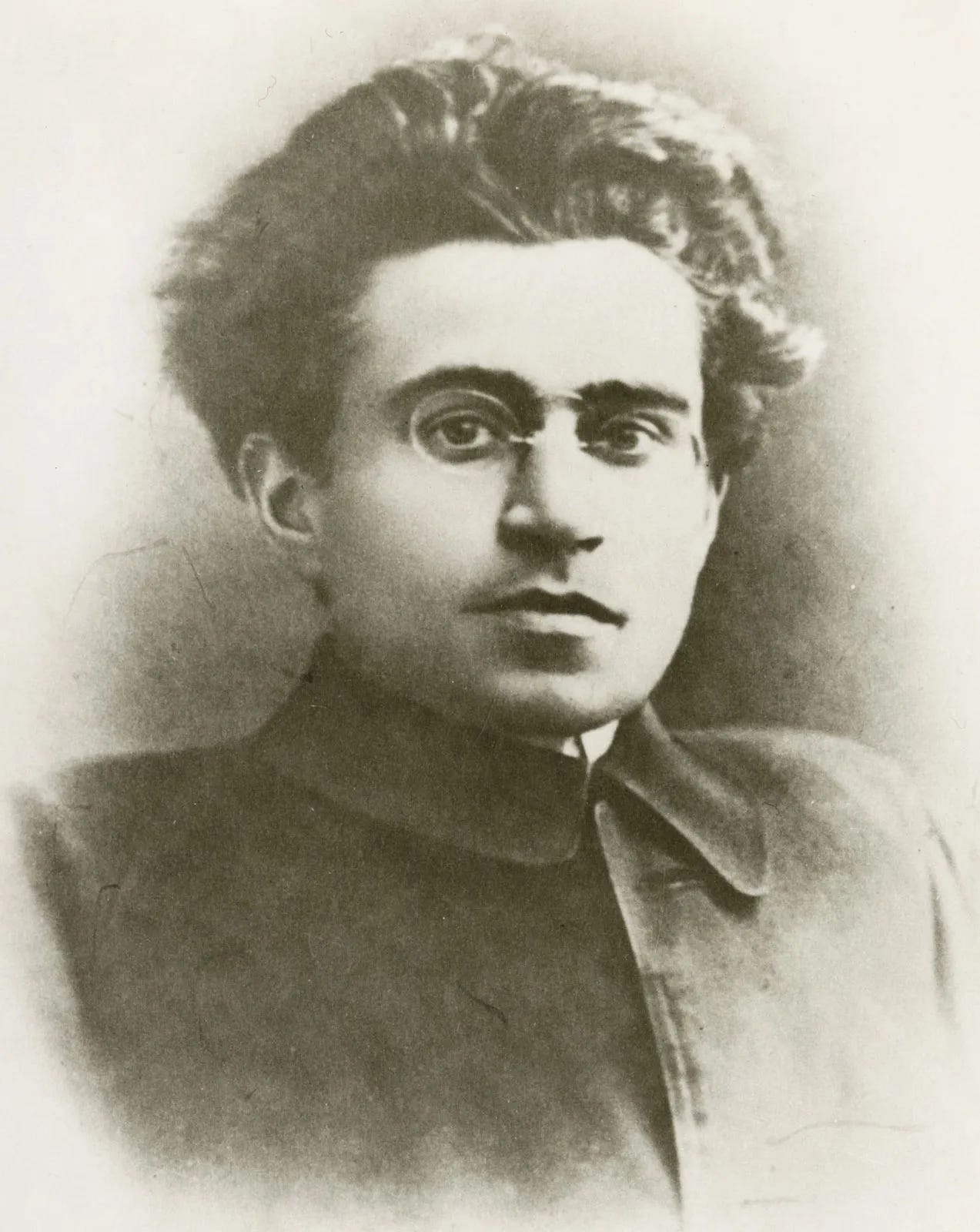

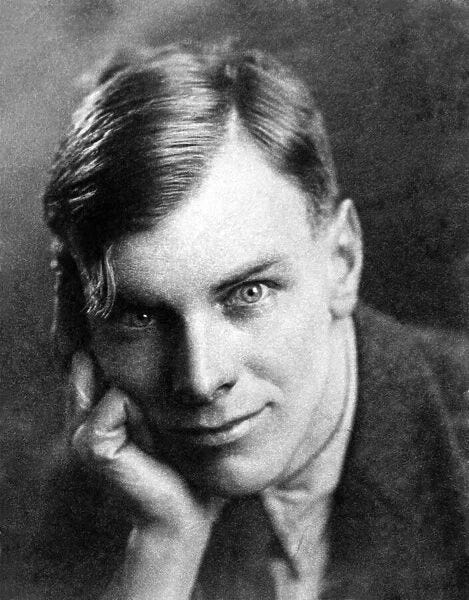

In the years following, two theorists would rise to prominence, Antonio Gramsci and Gyorgy Lukacs. Lukacs was considered the greatest socialist theorist since Karl Marx. His ideas were influential in most Marxist circles at the time, and as such, he was held as one who could pave the way forward for the ideology. At the core of his thinking remained the basic objectives of eliminated the family, religion, and private property - all seen as obstacles to the Marxist ideology. He did, however, offer some variations of Marxist and revolutionary utopian thought.

Another Communist political activist, Wilheim Münzehberg, along with Lukacs, explained that the working class were too accustomed to capitalism. Life in the West, their thinking goes, was actually too good, and people were too successful to feel the need to revolt. Only the rot and destruction of the culture that supported capitalism, could lead to Marxism. As Lukacs put it 'who will save us from western civilisation?’. Münzenberg was also quoted as saying that “We must organise the intellectuals and use them to make western civilisation stink. Only then, after they have corrupted all its values and made life impossible, can we impose the dictatorship of the proletariat.”

During these early days of the 20th Century, some intellectuals in America were warming to the Marxist model. This was due partly to the effects of earlier socialist groups, such as the English Fabian Socialists, however the Russian Revolution appears to have been the primary factor.

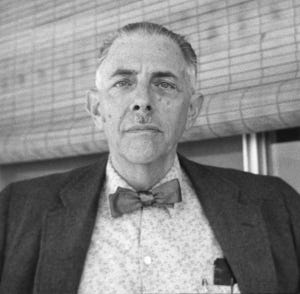

For example, prominent American philanthropist, John Dewey, admired the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, particularly the centralised, state controlled schooling and educational system they had established. Dewey himself said that the revolution had “a release of human powers on such an unprecedented scale that it is of incalculable significance not only for that country, but for the world”. Dewey would become highly influential in shaping the modern western schooling system, which he claimed needed to experience something akin to a Russian revolution. He believed that schools needed to be guided under the centralised control of the State, which would direct how individuals could think. In his writings, Dewey makes it clear that he (as with most Marxists) stands in opposition to private property, religion, and the family. In fact, he was outwardly hostile to such things, which he perceived as a threat to collectivism. As he put it, “During the transitional regime, the school cannot count upon the larger education to create in any single and whole-hearted way the required collective and cooperative mentality. The traditional customs and institutions of the peasant, his small tracts, his three-system farming, the influence of home and Church, all work automatically to create in him an individualistic ideology… despite the greater inclination of the city worker towards collectivism, even his social environment works adversely in many respects… Hence the great task of the school is to counteract and transform those domestic and neighborhood tendencies that are still so strong, even in a nominally collectivistic régime.”

It seems that powerful intellectuals like Dewey, inspired by the Russian Revolution, would have collectivism over their current system.

LUKACS

By 1919, Lukacs would be appointed Deputy Commissar for Culture in Hungary. The communist Government in power was led by Bela Kun, who had been planted in the country by Lenin following the Russian revolution. Lukacs first act as a deputy commissar was to begin what he called 'cultural terrorism’. This would be one of the first experiments, testing a new form of cultural manipulation, to bring about revolution. He rolled out a radical sex education program aimed at destroying the family. This program had far reaching effects in Hungarian society, which had been relatively conservative. In a matter of months, the Hungarian socialist government was overthrown. It would not be an exaggeration to say that outrage amongst the people primarily stemmed from Lukacs attempt to destroy Hungarian culture.

LENIN 1922

In 1922 there would come a pivotal point for Marxism, when Lenin would organise several top Marxist intellectuals to theorise on why class consciousness wasn’t working and how better to overthrow capitalism. Lukacs and Münzenberg were among the intellectuals meeting over these issues which inspired the formulation of a new Marxism, more capable of overthrowing what had been a rather successful capitalism.

At this point, communist organisations in America were relatively small, yet surprisingly organised. America was technically at war with the Bolsheviks, having aided White Russian forces in the Russian Civil War. Nevertheless domestic communist groups were steadily on the rise. In 1922, their activities soon came to the attention of law enforcement.

Police raided a meeting of top communists in Bridgman. Many secret documents were seized. One of the most surprising was a directive. Containing the signatures of several members of the Executive Committee of the communist international, the document stated that the American communist parties were indeed under the direction of the communist international. Another letter was found, this one from the American communists. It detailed how members must penetrate all working class and semi-working class organisations, such that they function as tools and auxiliaries of the party. During this time, the true party would remain underground. The directive from the international noted in the future, when possible, the communist parties should engage in real politics, as registered political parties. In the meantime the true party will remain underground, giving the illusion that communist movements exist, but are small and unorganised fringe groups.

FRANKFURT SCHOOL

The following year, in 1923, a research institute would be established for this exact purpose. Formed by Felix Weil, student of Karl Korsch, the newly established Institute sought to bring together Marxist intellectuals to discuss how to advance the revolution with new methods. Initially planning to name it the Institute For Marxist Research, Weil more cautiously gave it the vague title of Institute For Social Research and would be opened in 1924. Today, it is known as the Frankfurt School.

Lukacs' influence during the formative days of the Frankfurt School was significant. His clear message was to move Marxism away from economics and focus on culture. This sentiment was echoed by fellow Italian Marxist intellectual Antonio Gramsci. He believed that in the 20th century, Marxism could only succeed if it first infiltrated the cultural institutions: schools, universities, the media, the state apparatus.

The first head of the Frankfurt school was Carl Grunberg. At the opening the school, he was claimed to have said, “I too am one of the opponents of the economic, social, and legal order which has been handed down to us by history, and I too am one of the supporters of Marxism."

The institute’s ideology would be fleshed out some years later, when Grunberg was replaced by the rising Marxist intellectual Max Horkheimer. Horkheimer, inspired by Lukacs, worked to pivot the institute toward culture, rather than economics, while separating the institute from the tainted image of Soviet Marxism. He would lay the groundwork for what would become known as critical theory.

CRITICAL THEORY

The foundation of Horkheimer’s new theory was the idea that economic disparity and oppression were not the primary issue, as Marx had thought. Rather, oppression was manifest in a variety of areas in western society, be it sexual, religious, or other cultural norms. This theory was developed largely because western working class people lived good lives, and apparently were blind to their slavery, and their happiness was merely an illusion. Thus, critical theory, as the name suggests, was to criticise the existing society; to find supposed weak points, and expose their contradictions through a Marxist lens.

Horkheimer’s theory suggested that there were two types of revolution; the political revolution, and the cultural revolution. A political revolution could see the overthrow of a government and economic system, but would not address the old culture. A cultural revolution, however, could see everything overthrown, including every last remnant of the previous society and culture.

Horkheimer had said that logic is not “independent of content”. By this he meant that arguments are only logical if the content is about destroying western culture and illogical if it doesn’t. This sort of thinking set the Critical Theorists apart from the old Marxists, often referred to as the ‘classical’ or ‘vulgar’ Marxists. Unlike the classical Marxists, who’s primary concern beyond the proletariat revolution was the future of humanity, the Critical Theorists almost completely ignored discussion regarding the future. They became, it seems, profoundly nihilistic.

By the 1930s the Frankfurt School was under threat. The National Socialists took hold of power in Germany and threatened to shut down all communist threats. At this same time, two new members to the Frankfurt School, Theodore Adorno and Erich Fromm, were tasked with finding a safe-haven for the institute. Fromm succeeded in finding help in New York, largely thanks to support offered by the then president of Columbia University, and in 1935 the Frankfurt School was relocated to New York City. Before the move to America, the institute had largely been focused on criticising European culture. Now established in New York, the institute would apply their critical theory to their new home - America.

Communism had a strong foothold in America at this time, although not as entrenched as in Europe, and with a different approach. From an outsiders perspective, there was the impression of a fragmented socialist and Marxist movement in America with disunity among the many parties. This, however was just an illusion of weakness and incoherence, as the majority of these seemingly diverse parties had common managers, directing them fundamentally in the same direction. This proved highly effective in both entrenching communist ideas in America, as well as avoiding unwanted scrutiny from the government. As Bezmenov notes, these groups initially had ties to Moscow or the Communist International, but as time went on, they became more autonomous in their revolutionary aspirations.

From their base in New York, the critical theorists would analyse the situation in Europe, coming to the conclusion that Karl Marx was wrong in his assumption that capitalism would inevitably collapse and give way to socialism. The new theory was that capitalism would become fascism, unless redirected, through revolution, to socialism. Thus, anyone who wished to uphold the existing culture, or simply did not wish to align themselves with the socialist revolutionaries, were labelled ‘Fascists’, or at the very least, enablers of fascism; an insult which continues to this day.

Many of these concepts were published in “The Authoritarian Personality”, in 1950, written by Theodor Adorno and fellow researchers at University of California, Berkeley. Adorno and his co-authors diagnose authoritarianism as a personality type, identified by 9 traits on what they called a F scale, or fascist scale. As it so happened, the traits of the authoritarian personality described someone who would reject the tenants of critical theory. Those who held to more conservative values and rejected progressive concepts, for example, would likely be considered to be (or border on) the so-called authoritarian personality type. With little respect for the culture of their new home in United States, Adorno and company attacked Americans, insinuating that so called fascist traits were deeply rooted in the American people. Americans, who sought to preserve their values, were seen as unhinged, authoritarian, or worse.

Before America entered the war with Germany, Max Horkheimer had already begun writing up proposals for the reeducation (or mental transformation) of the German people. At the same time, a new member of the Frankfurt School, Herbert Marcuse, had begun making a name for himself by working on similar theories. Fortunately for these critical theorists, many within positions of power held similar utopian ideologies, ushering the likes of Horkheimer and Marcuse into places of significant influence.

By 1942, Marcuse was employed by the US Navy’s Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the CIA, thanks to friends in high places, despite the fact that Marcuse was under close surveillance by the FBI, who rightly suspected him to be a communist infiltrator. Nevertheless, thanks to his powerful friends and careful use of rhetoric, Marcuse and his colleagues continued their work unhindered.

Because of collaboration with the Soviets, American communists were now viewed as mere patriots. In fact, top down coercion prevented serious investigations into communist manipulation during this period. President Roosevelt himself gave orders to the Civil Service Commission, restricting them from questioning whether members of the federal service were communists or not.

Someone who noted subversion occurring during this period was Robert Morris, who headed a Counter-intelligence unit of the 3rd naval district, Washington. He notes that a key moment came when president Roosevelt ordered to Navy to allow communists in, specifically with the clearance to work as radar operators with access to classified information. He then received information from a communist defector - Victor Kravchenko - that this information - much of which was intended to help the soviets fight the Germans - was instead being catalogued for a war with America. Morris took this information to his superiors. In response, he was removed from his intelligence post and sent to the Pacific.

The head of the OSS during WW2 was William Donovan. During this period, Donovan is known to have been in contact with Eugene Dennis - a communist party functionary - and used this connection to employ officers directly from the communist party. The bias was immediate. In German occupied Yugoslavia, OSS funding, support, and so forth was restricted from going to the nationalists who were fighting the Germans - namely the Chetniks under Draza Mihailovic. They would receive no help. Instead, funding would flow directly to the communists, led by Josef Tito. After the war, axis prisoners and others who did not wish to live under communism attempted to surrender to the Americans and the Chetniks. However, orders from above stated that all such people must be given over the Titos communists, or the Red Army, thus ensuring an eastern European communist stronghold. Today, this is known as Operation Keelhaul; over 2 million people were forcibly repatriated to the communists, including those who had lived in America and England from before the Russian Revolution 30 years earlier. The majority were civilians with families. Alexander Solzhenitsyn recalls that mass suicides were common amongst these families; those that went to the Soviets were sent to gulags - as were most Soviet troops who had been further westward than Berlin during the war - whilst those who were handed over to Titos communists were brutally mass executed. American soldiers would be used to round up and hand over these anti-communists, all of whom were not even in Soviet controlled territory, but lived throughout Europe, and essentially destroyed any anti-communist movements emerging in Europe after the war.

This inexcusable bias was noted by the FBI, who approached general Donovan. When asked if he knew that there were communists within the OSS, he replied “Of course I know, that’s why I hired them”. During this time, Roosevelt had also extended this so far as to offer the Soviets the opportunity to set up an NKVD office in Washington. This was noted by Otto Otepka, a veteran internal security specialist.

This was the perfect situation for a communist incursion into the state’s institutions. By the late 1940s, it could be fair to say that the highest echelons had been infiltrated and in some cases resulting in startling breaches of national security.

With the defeat of Germany looking inevitable, Marcuse was joined at the OSS by two other critical theorists; Otto Kirkheimer, and Franz Neumann. at the same time, Horkheimer and Adorno had been offered similar powerful positions, giving Horkheimer a chance to put forth his radical ideas on the authoritarian personality. Horkheimer, and the rest of the theorists in the OSS, would work to plan out what would become known as the denazification process. this process would offer the critical theorists a chance to spread their ideology across a huge part of Europe, and later America. The organisation set up for the task of denazification was the Institute on Reeducation of the Axis Countries, run under the Psycholohical warfare division. one of the first tasks was a mass censorship campaign across Germany with over 30,000 books were banned with all copies destroyed, with possession of such books punishable as an offence. Thousands of book dealers were banned, hundreds of cinemas, publishers, theatres and magazines were also forcibly shut down. In this manner, the initial push by the reeducation institute was practically no different to the policies enacted by the Germans.

However, it would be the next stage of the process which would truly allow for a communist incursion both into Europe and America. Using the theories on authoritarian personality types put forward by Marcuse, a campaign was run in which collective guilt was forced upon the German people. A key detail here is that this guilt was not merely extended to those who actively worked for the Nazis, but was explicitly extended to the German people more broadly. This was explicitly noted by Sidney Bernstein, head of the psychological warfare division, who was quoted as saying that the goal of the reeducation program in Europe was "to shake and humiliate the Germans and prove to them beyond any possible challenge that these German crimes against humanity were committed and that the German people - not just the Nazis and the SS - bore responsibility." Rather than merely put the destructive ideas of the Nazis on trial for all to see, the German people were instead targeted broadly - regardless of whether or not they had supported the Nazis. This contradicted what one would likely considered the proper way to go about reeducation - by educating the German people on the inhumane outcome of their ideology. Instead the goal - on the part of the critical theorists of course - was to attempt to force the Germans to renounce their culture entirely, paving the way for a Marxist revolution. Thus it could be said that for the Critical Theorists this was not about denazification and fixing Germany at all, but rather enacting the will of the Marxist idea on a population.

In this way, the Critical Theorists and their friends in high places successfully took advantage of a chaotic situation - the need to defeat the Nazis - and used it as a grand stage to roll out their Marxist theories onto a population. Of course, the implication here - which is noted by former Marxist turned anti-Marxist Paul E Gottfried - is that the reeducation process - which included criticism of ones own culture - would soon expand outwards from Germany. It would then be used to implicate all of European culture, and eventually even American culture, until finally all forms of Western, capitalist culture fell under the same label; fascist, or fascist enabling.

After the war the doors were largely left open for high level manipulation in America. As Bezmenov himself notes, the demoralisation process against America required action from within, and once this had been achieved, American demoralisation was spontaneous and no longer required Moscow to guide it. It is clear that communist incursions into the state apparatus in America had been happening since at least the 1920s. Certainly by that point, the media had been infiltrated, as was personified by New York Times columnist Walter Duranty, who won a Pulitzer prize for supposedly disproving the soviet orchestrated Ukrainian famine. in actuality, Duranty was on the payroll of Joseph Stalin, and was ideologically aligned with the Soviets.

During the 1933 Ukrainian famine - or Holodomor - Soviet authorities locked down the region, and began collectivisation. This was to prevent information from leaving. Rumours did indeed escape however, and these rumours spread across the capitalist West. In response, Duranty famously wrote an article claiming that there was no famine in Ukraine, and that the Ukrainian citizens were - as he put it - 'hungry, not starving'. In actuality, many millions were dying. Two individuals - a communist turned anti-communist by the name of Malcolm Muggeridge - and journalist Garreth Jones both snuck into Ukraine, exposing this harsh reality. However, ideologues within the western media apparatus prevented these unfortunate truths from going mainstream, instead siding with Duranty and his claims. Duranty would receive a Pulitzer prize for his so called journalism, which has never been revoked till this day. This exemplifies a general trend in the 1930s, in which Marxist ideas - not yet tainted by the truth of the soviet experiment - grew in popularity. This only increased during the war.

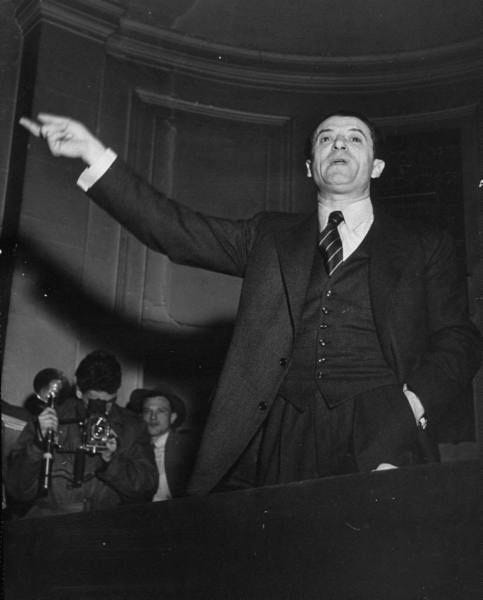

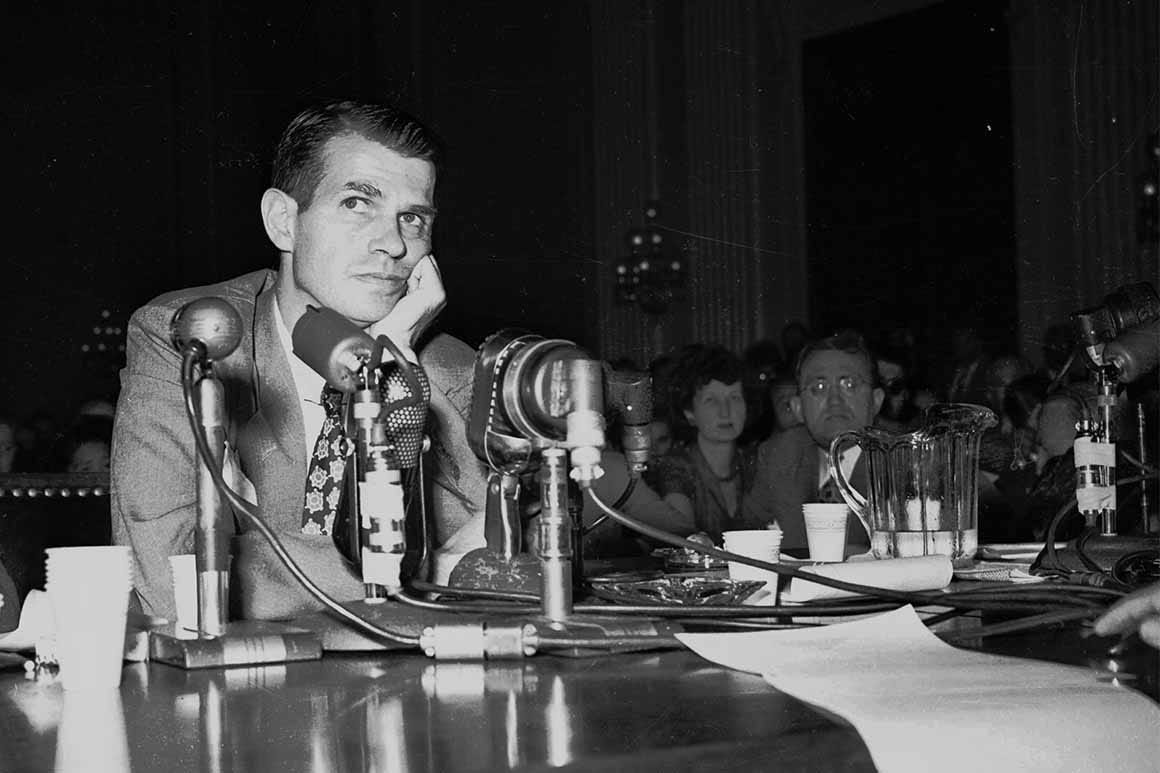

An early public defector was Whittaker Chambers. He revealed that he had secretly been a communist member for over a decade, during which time he had worked as liaison between high ranking members of the federal government, who were actually communists.

Both Chambers and Elizabeth Bentley had both testified that four communist cells existed in positions of power; the first was the Ware Cell - run by Harold Ware of the Department of Agriculture. The second was the Silvermaster Cell - run by Nathan Gregory Silvermaster, form the Farm Security administration.The third was the Purlo Cell - run by Victor Perlo of the Treasury Department. Bentley and Chambers would implicate over 80 high ranking personnel that they were aware of. This included Roosevelt’s economic advisor Lauchlin Currie, economist for the Treasury Harold Glasser, and assistant secretary to the Treasury Harry Dexter White. White was one of the chief architects of both the World Bank and the IMF, and would author the Morgenthau Plan, considered part of the denazification plan, which explicitly set out to destroy all German manufacturing ability after the war, including heavy industry. Herbert Hoover investigated the plan, and calculated that it would kill 25 million Europeans after the war if it was enacted. Fortunately, it was rejected and replaced by the more moderate Marshall Plan. This revelation to the public also angered then president Harry Truman, who did not repeal the pro-communist stance taken by Roosevelt before him.

The fourth cell named was that of Alger Hiss. Initially a law clerk in the Supreme Court, he would then join the Department of Agriculture, and finally the State Department, becoming assistant Secretary of State. Here he exerted influence, becoming official advisor to Roosevelt during the Yalta Conference, giving insight into how to reshape postwar Europe and China. After the war, he oversaw the writing of the United Nations Charter, acting as Chairman and Secretary General during its founding meeting. It is worth noting that in the UN General Assembly after this time, the Soviets were given three votes in matters, while America only had one vote, and the Soviets would always be given charge of UN military operations. It is now obvious why this was the case. Yet as early as 1939 Hiss had been named as a communist agent by both Chambers and the French intelligence service, and ignored. He would be implicated a further three times; first by Elizabeth Bentley in 1945, then by a soviet defector in 1946, and lastly by defected and former member of the Frankfurt school Hede Massing in 1949. Only this last time was attention paid. Yet despite this, president Truman vehemently stood against any accusations, going so far as to forbid the executive branch of government from handing over records on employee personnel.

Alger Hiss was far from the most powerful member at this point. Elizabeth Bentley noted that when she was a member, she was aware that two other cells existed in Washington. These groups were so important that other members were not allowed to know of their identities. These groups were never exposed.

How Communists Took Over America (Part 2)

Part 2 of a three part series on communist activity in America during the 20th Century. See part 1 here:Our work is increasingly restricted to earn any revenue on YouTube. Consider becoming a paid subscriber to help us create more video content for you.

How Communists Took Over America (Part 3)

Part 3 of a three part series on communist activity in America during the 20th Century. See part 1 here | part 2 hereOur work is increasingly restricted to earn any revenue on YouTube. Consider becoming a paid subscriber to help us fund more video content for you.

Share this post